Inhaltsverzeichnis

5 Magnetic Circuits

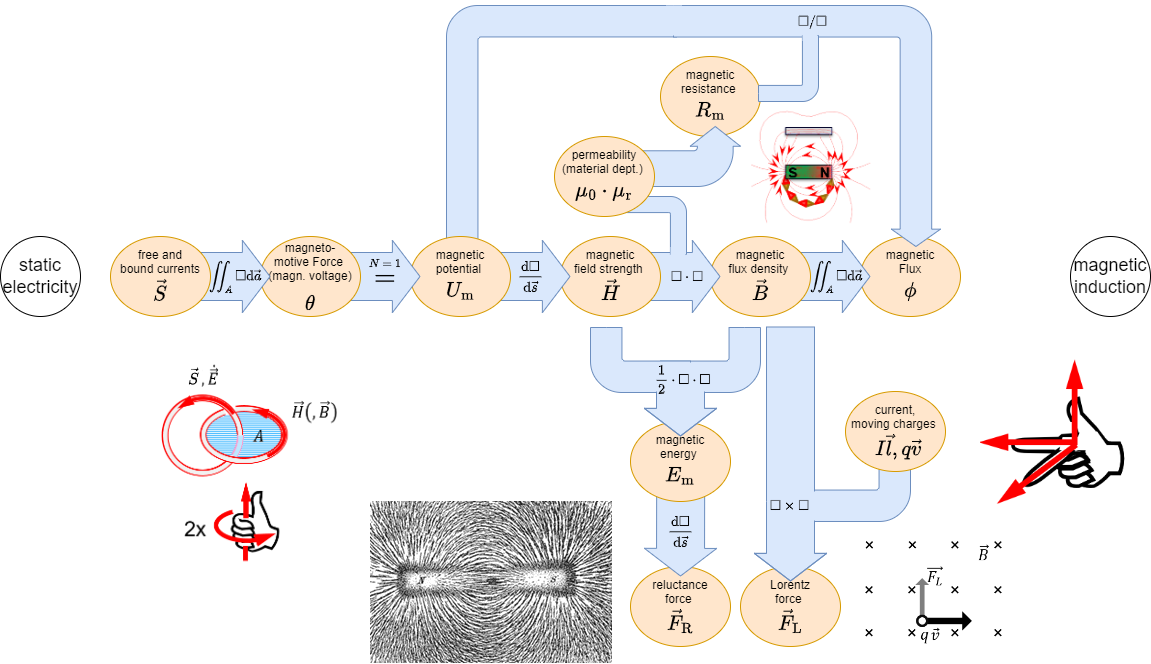

In the previous chapters, we got accustomed to the magnetic field. During this path, some similarities from the magnetic field to the electric circuit appeared (see Abbildung 1).

In this chapter, we will investigate how far we have come with such an analogy and where it can be practically applied.

5.1 Linear Magnetic Circuits

For the upcoming calculations, the following assumptions are made

- The relationship between $B$ and $H$ is linear: $B = \mu \cdot H$

This is a good estimation when the magnetic field strength lays well below saturation - There is no stray field leaking out of the magnetic field conducting material.

- The fields inside of airgaps are homogeneous. This is true for small air gaps.

One can calculate a lot of simple magnetic circuits when these assumptions are applied and focusing on the average field line are applied.

Two simple magnetic circuits are shown in Abbildung 3: They consist of

- a current-carrying coil

- a ferrite core

- an airgap (in picture (2) ).

These three parts will be investigated shortly:

Current-carrying Coil

For the magnetic circuit, the coil is parameterized only by:

- its number of windings $N$ and

- the passing current $i$.

These parameters lead to the magnetic voltage $\theta = N\cdot i$.

Ferrite Core

- The core is assumed to be made of ferromagnetic material.

- Therefore, the relative permeability in the core is much larger than in air ($\mu_{\rm r,core}\gg 1$).

- The ferrite core is also filling the inside of the current-carrying coil.

- The ferrite core conducts the magnetic flux around the magnetic circuit (and by this: also to the airgap)

Airgap

- The air gap interrupts the ferrite core.

- The width of the air gap is small compared to the dimensions of the cross-section of the ferrite core.

- The field in the air gap can be used to generate (mechanical) effects within the air gap.

An example of this can be the force onto a permanent magnet (see Abbildung 3 (3)).

With the above-mentioned assumptions the magnetic flux $\Phi$ must remain constant along the ferrite core, so $\Phi_{\rm core}=\rm const.$.

Since the magnetic field lines neither show sources nor sinks, also the flux passing over to the airgap must be $\Phi_{\rm airgap}=\Phi_{\rm core}=\rm const.$ This can also be seen in Abbildung 4 (1) ).

A different view of this is the closed surface $\vec{A}$ (Abbildung 4 (2)): Based on the examination in Recap of magnetic Field we know that the flux into the volume must be equal the flux out of the volume, or $\Phi_{\rm m} = \iint_{A} \vec{B} \cdot d \vec{A} = 0$.

The relationship $B=\mu \cdot H$, and $\mu_{\rm core}\gg\mu_{\rm airgap}$ lead to the fact that the ${H}$-Field must be much stronger within the airgap (Abbildung 4 (3)).

Magnetic Circuit in a Formula

Therefore, the following formula is given \begin{align*} \Phi_{\rm m} &= &\iint_A &\vec{B} \cdot d \vec{A} &= &{\rm const.} \\ &= & & B \cdot A &= &{\rm const.} \\ &= & &B_{\rm core} \cdot A_{\rm core} &= & B_{\rm airgap} \cdot A_{\rm airgap} = {\rm const.} \\ \end{align*}

The assumption, that there is that the field inside of airgap is homogeneous and there is no stray field lead to the fact, that $A_{\rm core} = A_{\rm airgap}$.

Therefore:

\begin{align*}

B_{\rm core} &= &B_{\rm airgap} = B \\

\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,core} H_{\rm core} &= &\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,airgap} H_{\rm airgap} = {{\Phi}\over{A}} \tag{5.2.1}

\end{align*}

Besides this, the magnetic field strength $H$ along one field line is directly given by: \begin{align*} \theta = N \cdot i &= \int_s \vec{H} d\vec{s} = \\ &= \int_{\rm core} \vec{H} d\vec{s} + \int_{\rm airgap} \vec{H} d\vec{s} \\ \end{align*}

With the assumtion of a linear and homogeneous $B$-Field and the width $\delta$ of the airgap, this leads to: \begin{align*} \theta = {H}_{\rm core} l_{\rm core} + {H}_{\rm airgap} \delta \tag{5.2.2} \end{align*}

With the prevoius formula $5.2.1$, this gets to: \begin{align*} \theta &= {{B}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,core}}} l_{\rm core} + {{B}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,airgap}}} \delta \\ &= {{\Phi \cdot l_{\rm core}}\over{A \cdot \mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,core}}} + {{\Phi \cdot \delta}\over{A \cdot \mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,airgap}}} \\ &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,core}}}{{l_{\rm core}}\over{A}} \cdot \Phi + {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r,airgap}}}{{\delta}\over{A}} \cdot \Phi \tag{5.2.3} \end{align*}

Comparing the formula $5.2.3$ with the ohmic resistance and resistivity of two resistors in series shows something interesting: \begin{align*} u &= &R_1 \cdot &i &+ &R_2 \cdot i \\ &= &\rho {{l_1}\over{A_1}} \cdot &i &+ &\rho {{l_2}\over{A_2}} \cdot i \end{align*}

This leads to:

- The magnetic voltage $\theta$ acts like the electic voltage $u$,

the magnetic flux $\Phi$ like the current $i$. - The linear relationship $\theta = f(\Phi)$ is also called Hopkinson's Law.

Notice:

- Also for the magnetic circuit one can set up a lumped circuit model (see Abbildung 5).

- Similar to Ohms law, there is a magnetic resistance or reluctance:

\begin{align*} \boxed{R_{\rm m} = {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}}} \end{align*} - The unit of $R_{\rm m}$ is $[R_{\rm m}]= [\theta]/[\Phi] = ~\rm 1 A / Vs = 1/H $

- The length $l$ is given by the mean magnetic path length (= average field line length in the core).

- Kirchhoff's laws (mesh rule and nodal rule) can also be applied:

- The sum of the magentic fluxes $\Phi_i$ in into a node is: $\sum_i \Phi_i=0 $

- The sum of the magnetic voltages $\theta_i$ along the average field line is: $\sum_i \theta_i=0 $

- The application of the lumped circuit model is based on multiple assumptions.

In contrast to the simplification for the electric current and voltage the simplification for the flux and magnetic voltage is not as exact.

Application and Limitations of the Circuit Interpretation

Notice:

„Recipe“ for solving magnetic circuits:- Watch out for individual magnetic resistances in the circuits:

- Separate the magnetic circuit into parts, where the permeability and area of the cross-section are constant.

For these parts $B$ and $H$ is constant. These parts will have individual magnetic resistances. - Each airgap also gets an individual magnetic resistance.

- Calculate the magnetic resistance by the mean magnetic path length through the individual parts.

- Calculate the magnetic circuit as a circuit.

- Magnetic voltages depict voltage sources; magnetic flux depicts currents.

- Use the known way to solve the circuit.

Be aware that the orientation of the current $I$ and the field strength $\vec{H}$ are also connected by the right-hand rule.

The results are only allowed as a first approximation. The following table shows the contrast between the electric and magnetic fields:

| Property | Electric Field | Magnetic Field |

|---|---|---|

| Materials | There are „pure“ isolators, which are completely non-conductive. | All materials have a permeability $>0$ |

| Sources | The source is concentrated (= there are field sources / electric charges) | The magnetic source (= coil) is distributed |

| Simplifications | The simplifications often work for good results (small wire diameter, relatively constant resistivity) | The simplification is often too simple (widespread beyond the mean magnetic path length, non-linearity of the permeability) |

Exercise 5.1.1 Coil on a plastic Core

A coil is set up onto a toroidal plastic ring ($\mu_{\rm r}=1$) with an average circumference of $l_R = 300 ~\rm mm$. The $N=400$ windings are evenly distributed along the circumference. The diameter on the cross-section of the plastic ring is $d = 10 ~\rm mm$. In the windings, a current of $I=500 ~\rm mA$ is flowing.

Calculate

- the magnetic field strength $H$ in the middle of the ring cross-section.

- the magnetic flux density $B$ in the middle of the ring cross-section.

- the magnetic resistance $R_{\rm m}$ of the plastic ring.

- the magnetic flux $\Phi$.

- $H = 667 ~\rm {{A}\over{m}}$

- $B = 0.84 ~\rm mT$

- $R_m = 3 \cdot 10^9 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

- $\Phi = 66 ~\rm nVs$

Exercise 5.1.2 magnetic Resistance of a cylindrical coil

Calculate the magnetic resistances of cylindrical coreless (=ironless) coils with the following dimensions:

- $l=35.8~\rm cm$, $d=1.90~\rm cm$

- $l=11.1~\rm cm$, $d=1.50~\rm cm$

The magnetic resistance is given by: \begin{align*} \ R_{\rm m} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}} \end{align*}

With

- the area $ A = \left({{d}\over{2}}\right)^2 \cdot \pi $

- the vacuum magnetic permeability $\mu_{0}=4\pi\cdot 10^{-7} ~\rm H/m$, and

- the relative permeability $\mu_{\rm r}=1$.

- $1.00\cdot 10^9 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

- $0.50\cdot 10^9 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

Exercise 5.1.3 magnetic Resistance of an airgap

Calculate the magnetic resistances of an airgap with the following dimensions:

- $\delta=0.5~\rm mm$, $A=10.2~\rm cm^2$

- $\delta=3.0~\rm mm$, $A=11.9~\rm cm^2$

- $3.9\cdot 10^5 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

- $2.0\cdot 10^6 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

Exercise 5.1.4 Magnetic Voltage

Calculate the magnetic voltage necessary to create a flux of $\Phi=0.5 ~\rm mVs$ in an airgap with the following dimensions:

- $\delta=1.7~\rm mm$, $A=4.5~\rm cm^2$

- $\delta=5.0~\rm mm$, $A=7.1~\rm cm^2$

- $\theta = 1.5\cdot 10^3 ~\rm A$, or $1000$ windings with $1.5~\rm A$

- $\theta = 2.8\cdot 10^3 ~\rm A$, or $1000$ windings with $2.8~\rm A$

Exercise 5.1.5 Magnetic Flux

Calculate the magnetic flux created on a magnetic resistance of $R_m = 2.5 \cdot 10^6 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$ with the following magnetic voltages:

- $\theta = 35 ~\rm A$

- $\theta = 950 ~\rm A$

- $\theta = 2750 ~\rm A$

- $\Phi =14 ~\rm µVs$

- $\Phi =0.38~\rm mVs$

- $\Phi =1.1 ~\rm mVs$

Exercise 5.1.6 Two-parted ferrite Core

A core shall consist of two parts, as seen in Abbildung 6. In the coil, with $600$ windings shall pass the current $I=1.30 ~\rm A$.

The cross sections are $A_1=530 ~\rm mm^2$ and $A_2=460 ~\rm mm^2$. The mean magnetic path lengths are $l_1 = 200 ~\rm mm$ and $l_2 = 130 ~\rm mm$.

The air gaps on the coupling joint between both parts have the length $\delta = 0.23 ~\rm mm$ each. The permeability of the ferrite is $\mu_r = 3000$. The cross-section area $A_{\delta}$ of the airgap can be considered the same as $A_2$

- Draw the lumped circuit of the magnetic system

- Calculate all magnetic resistances $R_{\rm m,i}$

- Calculate the flux in the circuit

- -

- magnetic resistances: $R_{\rm m,1} = 100 \cdot 10^3 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$, $R_{\rm m,1} = 75 \cdot 10^3 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$, $R_{{\rm m},\delta} = 400 \cdot 10^3 ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}$

- magnetic flux: $\Phi = 0.80 ~\rm mVs$

Exercise 5.1.7 Comparison with simplified Calculation

The magnetic circuit in Abbildung 7 passes a magnetic flux density of $0.4 ~\rm T$ given by an excitation current of $0.50 ~\rm A$ in $400$ windings. At position $\rm A-B$, an air gap will be inserted. After this, the same flux density will be reached with $3.70 ~\rm A$

- Calculate the length of the airgap $\delta$ with the simplification $\mu_{\rm r} \gg 1$

- Calculate the length of the airgap $\delta$ exactly with $\mu_{\rm r} = 1000$

- $\delta = 4.02(12) ~\rm mm$

- $\delta = 4.02(52) ~\rm mm$

Exercise 5.1.8 Coil on a ferrite Core with airgap

The choke coil shown in Abbildung 8 shall be given, with a constant cross-section in all legs $l_0$, $l_1$, $l_2$. The number of windings shall be $N$ and the current through a single winding $I$.

- Draw the lumped circuit of the magnetic system

- Calculate all magnetic resistances $R_{{\rm m},i}$

- Calculate the partial fluxes in all the legs of the circuit

5.2 Non-linear magnetic Circuits

not included in the present script

5.3 Mutual Induction and Coupling

Imagine charging your phone wirelessly by simply placing it on a charging pad. This seamless experience is made possible by the fascinating phenomenon of mutual induction and coupling between two coils.

This situation is depicted in Abbildung 9: When an alternating current flows through one coil (Coil $1$), it creates a time-varying magnetic field that induces a voltage in the nearby coil (Coil $2$), even though they are not physically connected. This mutual influence is governed by the principle of electromagnetic induction.

The key factor determining the strength of mutual induction is the mutual inductance ($M$) between the coils. It quantifies the magnetic flux linkage and depends on factors like the number of turns, current, and relative orientation of the coils.

While geometric properties play a role, the fundamental principle can be described using electric properties alone, making mutual induction a versatile concept with numerous applications, including:

- Wireless power transfer

- Transformers

- Inductive coupling in communication systems

- Inductive sensors

As we explore this chapter, we'll delve into the mathematical models, equations, and practical considerations of mutual induction and coupling, unlocking a world of innovative technologies that shape our modern lives. We explicitly try to answer the following questions:

- Which effect do the coils have on each other?

- Can we describe the effects with mainly electric properties (i.e. no geometric properties)

Effect of Coils on each other

- Windings $N_1$ of coil $1$ gets feed with current $i_1$.

- Coil $1$ generates change in flux $\Phi_{11}$

- Coil $2$ gets passed by part of the flux ($\Phi_{21}$)

- Stray flux $\Phi_{\rm S1}$ takes not part in coupling

- $\rightarrow$ Coils are magnetically coupled:

Flux $\Phi_{11}$ of coil $1$ gets divided into flux $\Phi_{21}$ in coil $2$ and stray flux $\Phi_{\rm S1}$ not passing coil $2$:

$\Phi_{11} = \Phi_{21} + \Phi_{\rm S1}$

- Induced voltage in coil $2$:

$ u_{\rm ind,2} = -{{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}}\Psi_{21} $

$\quad\quad = -N_2 \cdot {{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}}\Phi_{21} $

- Similar effect on coil $1$ due to a current $i_2$ through coil $2$:

$\Phi_{22} = \Phi_{12} + \Phi_{\rm S2}$

$ u_{\rm ind,1} = -N_1 \cdot {{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}}\Phi_{12} $

Linked Fluxes

For the single coil, we got the relationship between the linked flux $\Psi$ and the current $i$ as: $\Psi = L \cdot i$.

Now the coils also interact with each other. This must also be reflected in the relationship $\Psi_1 = f(i_1, i_2)$, $\Psi_2 = f(i_1, i_2)$:

\begin{align*}

\Psi_1 &= &\Psi_{11} &+ \Psi_{12} \\

\Psi_2 &= &\Psi_{22} &+ \Psi_{21} \\ \\

\Psi_1 &= &L_{11} \cdot i_1 &+ M_{12} \cdot i_2 \\

\Psi_2 &= &L_{22} \cdot i_2 &+ M_{21} \cdot i_1 \\

\end{align*}

With

- $L_{11}$ and $L_{22}$ as the self induction

- $M_{12}$ and $M_{21}$ as the mutual induction

The formula can also be described as:

The view of the magnetic flux is advantageous when effects like an acting Lorentz force is of interest. However, more often the coils couple electric circuits, like in a transformer or a wireless charger. Here, the effect on the circuits is of interest. This can be calculated with the induced electric voltages $u_{\rm ind,1}$ and $u_{\rm ind,2}$ in each circuit. They are given by the formula $u_{{\rm ind},x} = -{\rm d}\Psi_x /{\rm d}t$:

\begin{align*} \left( \begin{array}{c} u_1 \\ u_2 \end{array} \right) &= -{{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}} \left( \begin{array}{c} \Psi_1 \\ \Psi_2 \end{array} \right) \\ &= -\left( \begin{array}{c} L_{11} & M_{12} \\ M_{21} & L_{22} \end{array} \right) \cdot \left( \begin{array}{c} {{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}} i_1 \\ {{\rm d}\over{{\rm d}t}}i_2 \end{array} \right) \end{align*}

The main question is now: How do we get $L_{11}$, $M_{12}$, $L_{22}$, $M_{21}$?

Magnetic Circuit with two Sources

To get the self-induction and mutual induction of two interacting coils, we are going to investigate two coils on an iron core with a middle leg (see Abbildung 10).

There the stray flux of the previous situation is only located in the middle leg. This also means, that there is no stray flux outside of the iron core.

The Abbildung 10 shows the fluxes on each part. The black dots near the windings mark the direction of the windings, and therefore the sign of the generated flux.

All the fluxes caused by currents flowing into the marked pins are summed up positively in the core.

When there is a current flowing into a non-marked pin, its flux has to be subtracted from the others.

To get $L_{11}$ and $L_{22}$, we look back to the inductance $L$ of a long coil with the length $l$.

This was given in the chapter Self-Induction as

\begin{align*} L &= {{\Psi}\over{i}} \\ L &= \mu_0 \mu_{\rm r} \cdot N^2 \cdot {{A} \over {l}} \\ \end{align*}

In this case, $\Psi$ was the flux through the coil generated from the coil itself - here $L_{11}$ and $L_{22}$.

Comparing this formula with the magnetic resistance $R_{\rm m} = {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}} {{l}\over{A}}$ of the coil, one can conclude:

\begin{align} L = {{N^2 }\over {R_{\rm m,coil}}} \end{align}

Important here is, that we assumed no stray field. When taking this into account for calculating the self-induction the magnetic resistance $R_{\rm m,coil}$ ends op to be the resistance of the magnetic circuit, seen by the magnetic voltage source!

\begin{align} \boxed{L = {{N^2 }\over {R_{\rm m1}}}} \end{align}

The magnetic resistance $R_{\rm m1}$ in the example Abbildung 10 is $R_{\rm m1} = R_{\rm m,11} + (R_{\rm m,ss}||R_{\rm m,22})$. Based on this formula, the self-inductions $L_{11}$ and $L_{22}$ can be written with the magnetic resistances of the coils as:

\begin{align*} L_{11} &= {{N_1^2 }\over {R_{\rm m1}}} \\ L_{22} &= {{N_2^2 }\over {R_{\rm m2}}} \end{align*}

To get the effect of the mutual induction, a coupling coefficient $k$ is introduced. $k_{21}$ describes how much of the flux from coil $1$ is acting on coil $2$ (similar for $k_{12}$):

\begin{align*} k_{21} = \pm {{\Phi_{21}}\over{\Phi_{11}}} \\ \end{align*}

The sign of $k_{21}$ depends on the direction of $\Phi_{21}$ relative to $\Phi_{22}$! If the directions are the same, the positive sign applies, if the directions are opposite, the minus sign applies.

When $k_{21}=+100~\%$, there is no flux in the middle leg but only in the second coil and in the same direction as the flux that originates from the second coil.

When $k_{21}=-100~\%$, there is no flux in the middle leg but only in the second coil and in the opposite direction as the flux that originates from the second coil.

For $k_{21}=0~\%$ all the flux is in the middle leg circumventing the second coil, i.e. there is no coupling.

The mutual induction $M_{21}$ can be calculated as the fraction of the linked flux $\Psi_{11}$ in coil $2$ based on the current $i_1$ from the coil $1$ :

\begin{align*} M_{21} &= {{\Psi_{21}} \over{i_1}} \\ &= {{N_2 \cdot \Phi_{21}}\over{i_1}} \\ &= {{N_2 \cdot k_{21} \cdot \Phi_{11}}\over{i_1}} \\ &= {{N_2}\over{N_1}}k_{21} \cdot {{\Psi_{11}}\over{i_1}} \\ &= {{N_2}\over{N_1}}k_{21} \cdot L_{11} \\ &= {{N_2}\over{N_1}}k_{21} \cdot {{N_1^2 } \over {R_{\rm m1}}} \\ &= k_{21} \cdot {{N_1 \cdot N_2 }\over {R_{\rm m1}}} \\ \end{align*}

Note, that also $M_{21}$ and $M_{12}$ can be either positive or negative, depending on the sign of the coupling coefficients.

The formula is finally: \begin{align*} \left( \begin{array}{c} \Psi_1 \\ \Psi_2 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} {{N_1^2}\over{R_{\rm m1}}} & k_{12}\cdot{{N_1 \cdot N_2}\over{R_{\rm m2}}} \\ k_{21}\cdot{{N_1 \cdot N_2}\over{R_{\rm m1}}} & {{N_2^2}\over{R_{\rm m2}}} \end{array} \right) \cdot \left( \begin{array}{c} i_1 \\ i_2 \end{array} \right) \end{align*}

For most of the applications the induction matrix has to be symmetric1).

Therefore, the following applies:

- In General: the mutual inductance $M$ is: $M = \sqrt{M_{12}\cdot M_{21}} = k \cdot \sqrt {L_{11}\cdot L_{22}}$

- For symmetric induction matrix: The mutual inductances are equal: $M_{12} = M_{21} = M$

- The resulting total coupling $k$ is given as \begin{align*} k = \rm{sgn}(k_{12}) \sqrt{k_{12}\cdot k_{21}} \end{align*}

Exercise 5.3.1 Example for magnetic Circuit with two Sources

The magnetical configuration in Abbildung 11 shall be given.

The area of the cross-section is $A=9 ~\rm cm^2$ in all parts, the permeability is $\mu_r=800$, the length $l=12 ~\rm cm$ and the number of windings $N_1 = 400$, $N_2=300$.

1. Simplify the configuration into three magnetic resistors and 2 voltage sources. Draw the problem as an equivalent circuit

2. Calculate all magnetic resistances. Additionally, calculate the magnetic resistances $R_{\rm m1}$ and $R_{\rm m2}$ seen from the magnetic voltage source $1$ and $2$.

The magnetic resistance is summed up by looking at the circuit from the source $1$ (see Abbildung 13): \begin{align*} R_{\rm m1} &= R_{\rm m,11} + R_{\rm m,ss} || R_{\rm m,22} \\ \end{align*}

where the parts are given as \begin{align*} R_{\rm m,11} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{3\cdot l}\over{A}} &&= 398 \cdot 10^{3} ~\rm {{1}\over{H}} \\ R_{\rm m,ss} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{1\cdot l}\over{A}} &&= 133 \cdot 10^{3} ~\rm {{1}\over{H}} \\ R_{\rm m,22} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{2\cdot l}\over{A}} &&= 265 \cdot 10^{3} ~\rm {{1}\over{H}} \\ \end{align*}

With the given geometry, this leads to \begin{align*} R_{\rm m1} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}}\cdot \left(3 + {{1\cdot 2}\over{1 + 2}}\right) \\ &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}}\cdot {{11}\over{3}} &&= 486 \cdot 10^{3} ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}\\ \end{align*}

Similarly, the magnetic resistance $R_{m2}$ is \begin{align*} R_{\rm m2} &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}}\cdot {{11}\over{4}} &&= 365 \cdot 10^{3} ~\rm {{1}\over{H}}\\ \end{align*}

3. Calculate the self-inductions $L_{11}$ and $L_{22}$

4. Calculate the coupling factors $k_{12}$ and $k_{21}$.

The coupling factor $k_{21}$ is defined as „how much of the flux created by one coil ($\Phi_{11}$) crosses the other coil ($\Phi_{21}$) “: \begin{align*} k_{21} &= {{\Phi_{21}}\over{\Phi_{11}}} \end{align*}

For this, we look at the circuit considering only one coil („magnetic voltage source“), see Abbildung 14. Based on the image, we see that the flux $\Phi_{11}$ divides into $\Phi_{S1}$ and $\Phi_{21}$ based on the magnetic resistance $\Phi_{\rm m,SS}$ and $\Phi_{\rm m,22}$. In step 2, we have calculated that $R_{\rm m,22}$ is twice $R_{\rm m,SS}$. So from the incoming flux, only $1/3$ reaches $R_{\rm m,22}$ and - by this - „crosses the other coil“.

Therefore, the coupling factor $k_{21}$ is: $k_{21}= 1/3$.

A similar approach leads to $k_{12}$ with $k_{12}= 1/4$.

5. Calculate the mutual inductions $M_{12}$, and $M_{21}$,

Exercise E 5.3.2 Wireles Charging

For Electric vehicles, sometimes wireless charging systems are employed. These use the principle of mutual inductance to transfer power from a charging pad on the ground to the vehicle's battery pack.

This system consists of two coils: a transmitter coil embedded in the charging pad and a receiver coil mounted on the underside of the vehicle.

- The transmitter coil has a self-inductance of $L_{\rm T} = 200 ~\rm \mu H$.

- The receiver coil has a self-inductance of $L_{\rm R} = 150 ~\rm \mu H$.

- The mutual inductance between the coils at this distance is measured to be $M = 20 ~\rm \mu H$ - when the vehicle is properly aligned over the charging pad.

1. Calculate the coupling coefficient $k$ between the transmitter and receiver coils when the vehicle is properly aligned over the charging pad.

The given self-inductances are $L_{\rm T} = L_{11}$, $L_{\rm R} = L_{22}$.

By this, the following formula can be applied:

\begin{align*} M = k \cdot \sqrt{L_{\rm T} \cdot L_{\rm R}} \end{align*}

Therefore, $k$ is given as: \begin{align*} k = {{M}\over{ \sqrt{ L_{\rm T} \cdot L_{\rm R} } }} \end{align*}

2. If the vehicle is misaligned by 10 cm from the center of the charging pad, the mutual inductance drops to $M = 12 ~\rm \mu H$. Calculate the new coupling coefficient in this misaligned position.

Effects in the electric Circuits

- Whenever two coils are magnetically coupled, not only the self-induction $L$ but also the mutual induction $M$ applies.

- Based on the currents $i_1$, $i_2$ in the two circuits, the induced voltages are given by:

\begin{align*} u_1 &= L_{11} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} &+ M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ u_2 &= M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} &+ L_{22} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ \end{align*}

It is important to consider the polarity of the fluxes for the calculation in circuits (see Abbildung 15). The sign of the mutual induction is influenced by

- the direction of the windings, and

- The orientation/counting of the current in the circuit.

positive Polarity

The polarity is positive when both currents either flow into or out of the dotted pin (see Abbildung 16).

Abb. 16: Example Circuits with positive Polarity

In this case, the mutual induction is positive $(M>0)$.

The formula of the shown circuitry is then: \begin{align*} u_1 &= R_1 \cdot i_1 &+ L_{11} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} &+ M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ u_2 &= R_2 \cdot i_2 &+ L_{22} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} &+ M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ \end{align*}

Negative Polarity

The polarity is negative when only one current flows into the dotted pin and the other one out of the dotted pin (see Abbildung 17).

In this case, the mutual induction is negative $(M<0)$*.

The formula of the shown circuitry is then: \begin{align*} u_1 &= R_1 \cdot i_1 &+ L_{11} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} & + M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ u_2 &= R_2 \cdot i_2 &+ L_{22} \cdot {{{\rm d}i_2}\over{{\rm d}t}} & + M \cdot {{{\rm d}i_1}\over{{\rm d}t}} & \\ \end{align*}

Exercise 5.3.3 toroidal Core with two Coils

A toroidal core (ferrite, $\mu_{\rm r} = 900$) has a cross-sectional area of $A = 500 ~\rm mm^2$ and an average circumference of $l=280 ~\rm mm$. At the core, there are two coils $N_1=500$ and $N_2=250$ wound. The currents on the coils are $I_1 = 250 ~\rm mA$ and $I_2=300 ~\rm mA$.

- The coils shall pass the currents with positive polarity (see the image A in Abbildung 18). What is the resulting magnetic flux $\Phi_{\rm A}$ in the coil?

- The coils shall pass the currents with negative polarity (see the image B in Abbildung 18). What is the resulting magnetic flux $\Phi_{\rm B}$ in the coil?

The resulting flux can be derived from a superposition of the individual fluxes $\Phi_1(I_1)$ and $\Phi_2(I_2)$, or alternatively by summing the magnetic voltages in the loop ($\sum_x \theta_x = 0$).

Step 1 - Draw an equivalent magnetic circuit

Since there are no branches, all of the core can be lumped into a single magnetic resistance (see Abbildung 19).

Step 2 - Get the absolute values of the individual fluxes

Hopkinson's Law can be used here as a starting point.

It connects the magnetic flux $\Phi$ and the magnetic voltage $\theta$ on the single magnetic resistor $R_\rm m$.

It also connects the single magnetic fluxes $\Phi_x$ (with $x = {1,2}$) and the single magnetic voltages $\theta_x$.

\begin{align*} \theta_x &= R_{\rm m} \cdot \Phi_x \\ N_x \cdot I_x &= {{1}\over{\mu_0 \mu_{\rm r}}}{{l}\over{A}} \cdot \Phi_x \\ \rightarrow \Phi_x &= \mu_0 \mu_{\rm r} {{A}\over{l}} \cdot N_x \cdot I_x = {{1}\over{R_{\rm m} }} \cdot N_x \cdot I_x \\ \end{align*}

With the given values we get: $R_{\rm m} = 495 {\rm {kA}\over{Vs}}$

Step 3 - Get the signs/directions of the fluxes

The Abbildung 20 shows how to get the correct direction for every single flux by use of the right-hand rule.

The fluxes have to be added regarding these directions and the given direction of the flux in question.

Therefore, the formulas are \begin{align*} \Phi_{\rm A} &= \Phi_{1} - \Phi_{2} \\ &={{1}\over{R_{\rm m} }} \cdot \left( N_1 \cdot I_1 - N_2 \cdot I_2 \right) \\ & = 0.25 ~{\rm mVs} - 0.15 ~{\rm mVs} \\ \Phi_{\rm B} &= \Phi_{1} + \Phi_{2} \\ &={{1}\over{R_{\rm m} }} \cdot \left( N_1 \cdot I_1 + N_2 \cdot I_2 \right) \\ & = 0.25 ~{\rm mVs} + 0.15 ~{\rm mVs} \end{align*}

- $0.10 ~\rm mVs$

- $0.40 ~\rm mVs$

5.4 Magnetic Energy

The magnetic field of a coil stores magnetic energy. The energy transfer from the electric circuit to the magnetic field is also the cause of the „current-damping“ effect of the inductor. The energetic turnover for charging an conductor from $i(t_0=0)=0$ to $i(t_1)=I$ is given by:

\begin{align*} W_m = \int_0^\infty u(t)\cdot i(t) {\rm d}t \end{align*}

With $u_L = L \cdot {\rm d}i/{\rm d}t$, this becomes:

\begin{align*} W_{\rm m} &= \int_0^\infty L\cdot {{{\rm d}i}\over{{\rm d}t}}\cdot i(t) {\rm d}t \\ &= \int_0^\infty L\cdot i(t) {\rm d}i \\ &= L\cdot \int_0^\infty i(t) {\rm d}i \\ &= L\cdot \left[ {{1}\over{2}}i^2\right]_0^I \\ \boxed{W_m = {{1}\over{2}}L\cdot I^2 } \end{align*}

magnetic Energy of a magnetic Circuit

With this formula also the stored energy in a magnetic circuit can be calculated. For this, the formula be rewritten by the properties linked flux $\Psi = N \cdot \Phi = L \cdot I$ and magnetic voltage $\theta=N \cdot I = \Phi \cdot R_{\rm m}$ of the magnetic circuit: \begin{align*} \boxed{W_{\rm m} = {{1}\over{2}} \Psi \cdot I = {{1}\over{2}} {{\Psi^2}\over{L}}= {{1}\over{2}}{{\Phi^2 }\over{N^2 \cdot L}} = {{1}\over{2}} \Phi^2 \cdot R_{\rm m} = {{1}\over{2}}{{\theta^2 }\over{R_{\rm m}}}} \end{align*}

magnetic Energy of a toroid Coil

The formula can also be used for calculating the stored energy of a toroid coil with $N$ windings, the cross-section $A$, and an average length $l$ of a field line.

By this, the following formulas can be used:

- For the magnetic voltage: $\theta = H \cdot l = N \cdot I $

- For the magnetic flux: $\Phi = B \cdot A $

With the above-mentioned formulas of the magnetic circuit, we get: \begin{align*} W_{\rm m} &= {{1}\over{2}} \Psi \cdot I \\ &= {{1}\over{2}}N \cdot B \cdot A \cdot {{H \cdot l}\over{N}} \\ &= {{1}\over{2}}B \cdot H \cdot A \cdot l \\ \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{W_{\rm m} = {{1}\over{2}}B\cdot H \cdot V} \end{align*}

The magnetic energy density $w_{\rm m}$ can therefore be calculated as: \begin{align*} w_{\rm m} &= {{W_{\rm m}}\over{V}} \\ &= {{1}\over{2}} B \cdot H \\ \end{align*}

This formula is also true for other types of coils.

generalized magnetic Energy

The general term to find the magnetic energy (e.g., for inhomogeneous magnetic fields) is given by \begin{align*} W_{\rm m} &= \iiint_V{w_{\rm m} {\rm d}V} \\ &= \iiint_V{\vec{B}\cdot \vec{H} {\rm d}V} \end{align*}

Application of the magnetic Energy

The circuit shown in Abbildung 21 shall now be investigated. The inductor shall be a toroid coil with $N$ windings, the cross-section $A$, and an average length $l$ of a field line.

The Kirchhoff mesh law leads to:

\begin{align*} u_{\rm s} = u_R + u_L \\ u_{\rm s} = R \cdot i + N {{{\rm d}\Phi}\over{{\rm d}t}} \end{align*}

Multiplying with $i$ and with $dt$, we get the principle of conservation of energy $dw = u \cdot i \cdot {\rm d}t$ for each small time step.

\begin{align*} u_{\rm s} \cdot i \cdot dt &= R \cdot i^2 \cdot {\rm d}t & + N {{{\rm d}\Phi}\over{dt}} \cdot i \cdot {\rm d}t & \\ dW &= {\rm d}W_R & + {\rm d}W_m & \end{align*}

In this way, we get the magnetic energy as: \begin{align*} dW_{\rm m} &= N {{{\rm d}\Phi}\over{{\rm d}t}} \cdot i \cdot {\rm d}t \\ W_{\rm m} &= \int {\rm d}W_{\rm m} \\ &= N \int_0^t {{{\rm d}\Phi}\over{{\rm d}t}} \cdot i \cdot {\rm d}t \\ &= N \int_0^ {\Phi} i \cdot {\rm d}\Phi \\ \end{align*}

In a toroid coil with a given cross-section $A$ the flux change ${\rm d}\Phi$ can only be given as a change in the field $B$. Therefore, ${\rm d}\Phi = A \cdot {\rm d}B$. Additionally, we know that the magnetic voltage is given by $\theta(t) = N \cdot i = H(t) \cdot l$. Including this in the formula gives us:

\begin{align*} W_{\rm m} &= N \int_0^{B} I \cdot A \cdot {\rm d}B \\ &= \int_0^{B} H(B) \cdot l \cdot A \cdot {\rm d}B \\ &= V \int_0^{B} H(B) \cdot {\rm d}B \\ \end{align*}

We can conclude that the magnetic energy $W_{\rm m}$: $W_{\rm m}$ can be calculated from the $H$-$B$ curve by integrating the external magnetic field strength $H$ for each small step of the flux density ${\rm d}B$. This will be shown for the case of a linear magnetic behavior, a nonlinear behavior, and the situation with magnetic hysteresis shortly.

Circuit with linear magnetic Behavior

In Abbildung 22 the situation for a magnetic material with a linear relationship between $B$ and $H$ is shown. Given the maximum current $I_{\rm max}$ the maximum field strength $H_{\rm max}$ can be derived. In the circuit in Abbildung 21, the inductor will experience increasing and decreasing current. Therefore, the $B$-$H$-curve gets passed through positive and negative values of $H$ and $H$ along the line of $B=\mu H$.

The situation for integrating the area in the graph is also shown: For each step ${\rm d}B$, the corresponding value of the field strength $H$ has to be integrated. For $B_0=0$ to $B=B_{\rm max}$ the magnetic energy is

\begin{align*} W_{\rm m} &= V\int_0^{B} H(B) \cdot {\rm d}B \\ &= V\int_0^{B} {{B }\over{\mu}} \cdot {\rm d}B \\ &= {{1}\over{2}} V {{B^2}\over{\mu}} \\ &= {{1}\over{2}} V \cdot B \cdot H \\ \end{align*}

This situation is a good approximation for air or non-magnetic materials. However, it does not work well for ferrite materials, since they show nonlinear behavior and hysteresis.

Circuit with nonlinear magnetic Behavior

In Abbildung 22 the situation for a magnetic material with a nonlinear relationship between $B$ and $H$ is shown.

In this case, the permeability $\mu_{\rm r}$ is not a constant but can be represented as a function: $\mu_{\rm r}= f(B)$. Here, the formula $W_{\rm m} = V\int_0^{B} H(B) \cdot {\rm d}B$ also applies - so the magnetic energy is again the area between the curve and the $B$-axis. As an example, the situation of the field strength $H(t_1)=H_1$ is shown. This shall be the field strength after magnetizing the ferrite material to $H_{\rm max}$ (yellow arrows) and then partly demagnetizing the material again (blue arrow). The magnetization corresponds to an energy intake into the magnetic field, and the demagnetization to an energy outtake.

Moving along the $H$-$B$-curve, one can see that the energy intake and outtake are the same when coming back to a start point. This means that the magnetization and demagnetization take place lossless in this example. This is a good approximation for magnetically soft materials; however, it does not work for magnetically hard materials like a permanent magnet. Here, hysteresis also has to be considered.

Circuit with magnetic Hysteresis

Exercise

Exercise 5.1.9 Application: Shaded Pole Motor

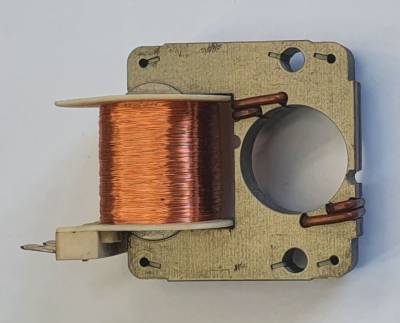

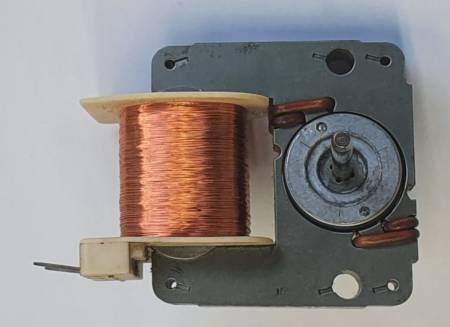

The Abbildung 25 and Abbildung 26 show a shaded pole motor of a commercial oven.

- Find out how this motor works - explicitly: why is there a preferred direction of the motor?

- In which direction does the shown motor run?

Exercise 5.1.10 Further exercise

The book DC Electrical Circuit Analysis - A Practical Approach (Fiore) has some nice exercises for beginning in the topic of magnetic circuits.

Further Information

An alternative interpretation of the magnetic circuits is the Gyrator–capacitor model. The big difference there is that the magnetic flux $\Phi$ is not interpreted as an analogy to the electric current $I$ but to the electric charge $Q$. This model can solve more questions; however, it is a bit less intuitive based on this course and less commonly used compared to the Magnetic_circuit, which was also presented in this chapter.

Moving a Plate into an Air Gap

Switch Reluctance Motor

Based on a wikimedia image from Hamidreza D (CC-SA 4.0)