Dies ist eine alte Version des Dokuments!

1. The Electrostatic Field

- Chapter 5. Electric Charges and Fields

- Chapter 6. Gauss's Law

- Chapter 7. Electrical Potential

- Chapter 8. Capacitance

From everyday life it is known that there are different charges and effects of charge. Abbildung 1 shows a chargable body, which can be charged via charge separation between the sole of the foot and the floor. The movement of the foot creates a negative excess charge in the person, which is gradually distributed throughout the body. If a pointed part of the body (e.g. finger) is brought into the vicinity of a charge reservoir without excess charges, a current can flow even through the air.

.

In the first chapter of the last semester we had already considered the charge as the central quantity of electricity and understood it as a multiple of the elementary charge. The mutual force action (the Coulomb-force) was already derived there. This is to be explained now more near.

First, however, a differentiation of various terms:

- Electrostatics describes the phenomena of charges at rest and thus of electric fields which do not change in time. Thus, there is no time dependence of the electrical quantities.

Mathematically, ${{df}\over{dt}}=0$ holds for any function of the electric quantities.

- Electrodynamics describes the phenomena of moving charges. Thus electrodynamics includes both electric fields that change with time and magnetic fields.

For the present state of the course, the simple explanantion shall be, that magnetic fields are based on a current or on a charge movement.

In electrodynamics, it is no longer valid for every function of the electric quantities, that the derivative is necessarily equal to zero.

At this chapter, only electrostatics are considered. The magnetic fields are therefore excluded here for the time being. Also electrodynamics is not considered in this chapter and is introduced step by step in the following chapters.

1.1 Electric Field and Field Lines

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know that an electric field is formed around a charge.

- be able to sketch the field lines of electric fields.

- be able to represent the field vectors in a sketch when given several charges.

- be able to determine the resulting field vector by superimposing several field vectors using vector calculus.

- Be able to determine the force on a charge in an electrostatic field by applying Coulomb's law. Specifically:

- the force vector in coordinate representation

- the magnitude of the force vector

- the angle of the force vector

The simulation in Abbildung 2 was already briefly considered in the first chapter. Here, however, another point is to be dealt with.

In the simulation, please position a negative charge $Q$ in the middle and deactivate electric field. The latter is done via the hook on the right. Now the situation is close to reality, because a charge shows no effect at first sight.

For impact analysis, a sample charge $q$ is placed in the vicinity of the existing charge $Q$ (in the simulation, the sample charge is called „sensors“). It is observed that the charge $Q$ causes a force on the sample charge. This force can be determined with magnitude and direction at any point in space. The force acts in space in a similar way to gravity. The description of the state in space changed by the charge $Q$ is defined with the help of a field.

Abb. 2: setup for own experiments

.

Take a charge ($+1nC$) and position it.

Measure the field across a sample charge (a sensor).

The concept of a field shall now be briefly considered in a little more detail.

- The introduction of the field separates the cause from the effect.

- The charge $Q$ causes the field in space.

- The charge $q$ in space feels a force as an effect of the field.

- This distinction becomes important again in this chapter.

Also in electrodynamics for high frequencies this distinction becomes clear: the field there corresponds to photons, i.e. to a transmission of effects with the finite (light)speed $c$.

- As with physical quantities, there are different-dimensional fields:

- In a scalar field, a single number is assigned to each point in space.

E.g.- temperature field $T(\vec{x})$ on the weather map or in an object

- pressure field $p(\vec{x})$

- In a vector field, each point in space is assigned several numbers in the form of a vector. This reflects the action along the spatial coordinates.

For example.- gravitational field $\vec{g}(\vec{x})$ pointing to the center of mass of the object.

- electric field $\vec{E}(\vec{x})$

- magnetic field $\vec{H}(\vec{x})$

- If each point in space is associated with a two- or more-dimensional physical quantity - that is, a tensor - then this field is called a tensor field. Tensor fields are relevant in mechanics (e.g., stress tensor) but are not necessary for electrical engineering.

Vector fields can be stated as:

- Effects along spatial axes $x$,$y$ and $z$ (cartesian coordinate system).

- Effect in magnitude and direction vector (polar coordinate system)

Note:

- Fields describe a physical state of space.

- Here, a physical quantity is assigned to each point in space.

- The electrostatic field is described by a vector field.

The Electric Field

Thus, to determine the electric field, a measure of the magnitude and direction of the field is now needed. From the first chapter of the last semester the Coulomb Force between two charges $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ is known:

\begin{align*} F_C = {{{1} \over {4\pi\cdot\varepsilon}} \cdot {{Q_1 \cdot Q_2} \over {r^2}}} \end{align*}

In order to obtain a measure of the magnitude of the electric field, the force on a (fictitious) sample charge $q$ is now considered.

\begin{align*} F_C &= {{{1} \over {4\pi\cdot\varepsilon}} \cdot {{Q_1 \cdot q} \over {r^2}}} \\ &= \underbrace{{{1} \over {4\pi\cdot\varepsilon}} \cdot {{Q_1} \over {r^2}}}_\text{=independent of q} \cdot q \\ \end{align*}

The left part is therefore a measure of the magnitude of the field, i.e. independent of the size of the sample charge $q$. The magnitude of the electric field is thus given by

$E = {{1} \over {4\pi\cdot\varepsilon}} \cdot {{Q_1} \over {r^2}} \quad$ with $[E]={{[F]}\over{[q]}}=1 {{N}\over{As}}=1 {{N\cdot m}\over{As \cdot m}} = 1 {{V \cdot A \cdot s}\over{As \cdot m}} = 1 {{V}\over{m}}$

The result is therefore \begin{align*} \boxed{F_C = E \cdot q} \end{align*}

Note:

- The test charge $q$ is always considered to be positive (mnemonic: t = +). It is used only as a thought experiment and has no retroactive effect on the sampled charge $Q$.

- The sampled charge here is always a point charge.

Note:

A charge $Q$ generates an electric field $\vec{E}(Q)$ at a measuring point $P$. This electric field is given by- the magnitude $|\vec{E}|=\Bigl| {{1} \over {4\pi\cdot\varepsilon}} \cdot {{Q_1} \over {r^2}} \Bigl| $ and

- the direction of the force $\vec{F_C}$ which a sample charge on the measurement point $P$ experiences. This direction is given by the unit vector $\vec{e_r}={{\vec{F_C}}\over{|F_C|}}$ in that direction.

Be arware, that in English courses and literature $\vec{E}$ is simply called eletric field and the electric field strength is the magnitude $|\vec{E}|$. In German notation the elektische Feldstärke refers to $\vec{E}$ (magnitude and direction) and the elektrische Feld denotes the general presence of an electricstatic interaction (often without considering exact magnitude).

The direction of the electric field is switchable in Abbildung 2 via the „Electric Field“ option on the right.

The electric field can also be viewed again in this video.

Electric Field Lines

Electric field lines result as the (fictitious) path of a sample charge. Thus also electric field lines of several charges can be determined. However, these also result from a superposition of the individual effects - i.e. electric field - at a measuring point $P$.

The superposition is sketched in Abbildung 3: Two charges $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ act on the test charge $q$ with the forces $F_1$ and $F_2$. Depending on the positions, and charges the forces vary and also the resulting force. The simulation also shows a single field line.

For a full picture of the field lines between charges, one has to start with a single charge. The in- and outgoing lines on this charge are drawn in equidistance on the charge. This is also true for the situation with multiple charges. However there, the lines are not necessarily run radialy anymore. The test charge is influenced by all the single charges, and therefore the field lines can get bend.

In Abbildung 5 the field lines are shown. The additional „equipotential lines“ will be discussed later and can be deactivated by clearing the checkmark Show Equipotentials.

Try the following in the simulation:

- Get accustomed to the simulation. You can…

- … move the charges by drag and drop.

- … add another Charge with

Add»Add Point Charge. - … delete components with a right click onto it and

delete

- Where is the density of the field lines higher?

- How does the field between two positive charges look like? How between two different charges?

Note:

- The electrostatic field is a source field. This means there are sources and sinks.

- From the field line diagrams, the following can be obtained:

- Direction of the field ($\hat{=}$ tangent to the field line).

- Magnitude of the field ($\hat{=}$ number of field lines per unit area).

- The magnitude of the field along a field line is usually not constant.

Note:

Field lines have the following properties:- The electric field lines have a beginning (at a positive charge) and an end (at a negative charge).

- The direction of the field lines represents the direction of a force onto a positive test charge.

- There are no closed field lines in electrostatic fields. The reason for this can be explained considering the energy of the moved particle (see later subchapters).

- Electric field lines cannot cut each other: This is based on the fact that the direction of the force at a cutting point would not be unique.

- The field lines are always perpendicular to conducting surfaces. This is also based on energy considerations; more details later.

- The inside of a conducting component is always field free. Also this will be discussed in the following.

Tasks

Task 1.1.1 Electric field example tasks

Task 1.1.2 Field lines

Sketch the field line plot for the charge configurations given in Abbildung 6.

Note:

- The overlaid picture is requested.

- Make sure that it is a source field.

You can prove your result with the simulation Abbildung 3.

1.2 Electric charge and Coulomb force (reloaded)

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- be able to determine the direction of the forces using given charges.

- be able to represent the acting force vectors in a sketch.

- be able to determine a force vector by superimposing several force vectors using vector calculus.

- be able to state the following quantities for a force vector:

- Force vector in coordinate representation

- magnitude of the force vector

- Angle of the force vector

The electric charge and Coulomb force has already been described in last semester. However, some points are to be caught up here to it.

Direction of the Coulomb force and Superposition

In the case of the force, only the direction has been considered so far, e.g. direction towards the sample charge. For future explanations it is important to include the cause-effect in the naming. This is donw by giving the correct labeling the subsript of the force. In Abbildung 7 (a) and (b) the convention is shown: A force $\vec{F}_{21}$ acts on charge $Q_2$ and is caused by charge $Q_1$. As a mnemonic you can remember „tip-to-tail“ (first the effect, then the cause).

Furthermore, several forces on a charge can be superimposed to a resulting force.

Strictly speaking, it must hold that $\varepsilon$ is constant in the structure. For example, the resultant force in Abbildung 7 Fig. (c) on $Q_3$ becomes equal to: $\vec{F_3}= \vec{F_{31}}+\vec{F_{32}}$.

Abb. 7: direction of coulomb force

.

Geometric Distribution of Charges

In previous chapters only single charges (e.g. $Q_1$, $Q_2$) were considered.

- The charge $Q$ was previously reduced to a point charge.

This can be used, for example, for the elementary charge or for extended charged objects from a large distance. The distance is sufficiently large if the ratio between the largest object extent and the distance to the measurement point $P$ is small. - If the charges are lined up along a line, this is called a line charge.

Examples of this are a straight trace on a circuit board or a piece of wire. Furthermore, this also applies to an extended charged object, which has exactly an extension that is no longer small in relation to the distance. For this purpose, the charge $Q$ is considered to be distributed over the line. Thus, a (line) charge density $\rho_l$ can be determined:$\rho_l = {{Q}\over{l}}$

or, in the case of different charge densities on subsections:

$\rho_l = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta l}} \rightarrow \rho_l(l)={{d}\over{dl}} Q(l)$

- It is spoken of an area charge when the charge distributed over an area.

Examples of this are the floor or a plate of a capacitor. Again, an extended charged object can be considered if there are two extensions which are no longer small in relation to the distance (e.g. surface of the earth). Again, a (surface) charge density $\rho_A$ can be determined:$\rho_A = {{Q}\over{A}}$

or if there are different charge densities on partial surfaces:

$\rho_A = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta A}} \rightarrow \rho_A(A) ={{d}\over{dA}} Q(A)={{d}\over{dx}}{{d}\over{dy}} Q(A)$

- Finally, a space charge is the term for charges that span a volume.

Here examples are plasmas or charges in extended objects (e.g. the doped volumes in a semiconductor). As with the other charge distributions, a (space) charge density $\rho_V$ can be calculated here:$\rho_V = {{Q}\over{V}}$

or for different charge density in partial volumes:

$\rho_V = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta V}} \rightarrow \rho_V(V) ={{d}\over{dV}} Q(V)={{d}\over{dx}}{{d}\over{dy}}{{d}\over{dz}} Q(V)$

In the following, area charges and their interactions will be considered.

Types of Fields depending on the Charge Distribution

There are two different types of fields:

In homogeneous fields, magnitude and direction are constant throughout the field range. This field form is idealized to exist within plate capacitors. e.g., in the plate capacitor (Abbildung 9), or in the vicinity of widely extended bodies.

For inhomogeneous fields, the magnitude and/or direction of the electic field changes from place to place. This is the rule in real systems, even the field of a point charge is inhomogeneous (Abbildung 10).

Tasks

Task 1.2.1 Multiple Forces on a Charge I (exam task, ca 8% of a 60-minute exam, WS2020)

Given is the arrangement of electric charges in the picture on the right.

The following force effects result:

$F_{01}=-5 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{02}=-6 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{03}=+3 ~\rm{N}$

Calculate the magnitude of the resulting force.

- How have the forces be prepared, to add them correctly?

The forces have to be resolved into coordinates. Here, it is recommended to use an orthogonal coordinate system ($x$ and $y$).

The coordinate system shall be in such a way, that the origin lies in $Q_0$, the x-axis is directed towards $Q_3$ and the y-axis is orthogonal to it.

For the resolution of the coordinates, it is necessary to get the angles $\alpha_{0n}$ of the forces with respect to the x-axis.

In the chosen coordinate system this leads to: $\alpha_{0n} = \arctan(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x})$

$\alpha_{01} = \arctan(\frac{3}{1})= 1.249 = 71.6°$

$\alpha_{02} = \arctan(\frac{4}{3})= 0.927 = 53.1°$

$\alpha_{03} = \arctan(\frac{0}{3})= 0= 0°$

Consequently, the resolved forces are:

\begin{align*} F_{x,0} &= F_{x,01} + F_{x,02} + F_{x,03} && | \quad \text{with } F_{x,0n} = F_{0n} \cdot \cos(\alpha_{0n}) \\ F_{x,0} &= (-5~\rm{N}) \cdot \cos(71.6°) + (-6~\rm{N}) \cdot \cos(53.1°) + (+3~\rm{N}) \cdot \cos(0°) \\ F_{x,0} &= -9.54 ~\rm{N} \\ \\ F_{y,0} &= F_{y,01} + F_{y,02} + F_{y,03} && | \quad \text{with } F_{y,0n} = F_{0n} \cdot \sin(\alpha_{0n}) \\ F_{y,0} &= (-5~\rm{N}) \cdot \sin(71.6°) + (-6~\rm{N}) \cdot \sin(53.1°) + (+3~\rm{N}) \cdot \sin(0°) \\ F_{y,0} &= -2.18 ~\rm{N} \\ \\ \end{align*}

Task 1.2.2 Variation: Multiple Forces on a Charge II (exam task, ca 8% of a 60 minute exam, WS2020)

Given is the arrangement of electric charges in the picture on the right.

The following force effects result:

$F_{01}=-5 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{02}=-6 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{03}=+3 ~\rm{N}$

Calculate the magnitude of the resulting force.

Task 1.2.3 Variation: Multiple Forces on a Charge II (exam task, ca 8% of a 60 minute exam, WS2020)

Given is the arrangement of electric charges in the picture on the right.

The following force effects result:

$F_{01}=+2 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{02}=-3 ~\rm{N}$

$F_{03}=+4 ~\rm{N}$

Calculate the magnitude of the resulting force.

1.3 Work and Potential

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know how work is defined in the electrostatic field.

- be able to describe when work has to be performed and when it does not in the situation of a moving .

- know the definition of electric voltage and be able to calculate it in an electric field.

- understand why the calculation of voltage is independent of displacement.

- know what a potential difference is and recognise or be able to state equipotential surfaces (lines).

- be able to determine a potential curve for a given arrangement.

A detailed explanation can be found in the online Book 'University Physics II'. It is recommended to work through this independently.

In particular, this applies to:

- Chapter „7. electric potential“

Energy required to Displace a Charge in the electic Field

First, the situation of a charge in a homogeneous electric field shall be considered. As we have seen so far, the magnitude of $E$ is constant and the field lines are parallel. Now a positive charge $q$ is to be brought into this field.

If this charge would be free movable (e.g. electron in vacuum or in extended conductor) it would be accelerated along field lines. Thus its kinetic energy increases. Because the whole system of plates (for field generation) and charge however does not change its energetic state - thermodynamically the system is closed. From this follows: if the kinetic energy increases, the potential energy must decrease.

Abb. 11: Observation of work in a homogeneous electric field

It is known from mechanics, that the work done (thus energy needed) is defined by force one needs to move along a path.

In a homogeneous field, the following holds for a force producing motion along a field line from $A$ to $B$ (see Abbildung 11):

\begin{align*}

W_{AB} = F_C \cdot s

\end{align*}

For a motion perpendicular to the field lines (i.e. from $A$ to $C$) no work is needed - so $W_{AC}=0$ results - because the formula above is only true for $F_C$ parallel to $s$. The motion perpendicular to the field lines is similar to the movement of a weight in the gravitational field at the same height. Or more illustrative: It is similar to walk at the same floor of a house. There, too, no energy is released or absorbed with regard to the field. For any direction through the field the part of the path has to be considered, which is parallel to the field lines. This results from the angle $\alpha$ between $\vec{F}$ and $\vec{s}$: \begin{align*} W_{AB} = F_C \cdot s \cdot cos(\alpha) = \vec{F_C}\cdot \vec{s} \end{align*}

The work $W_{AB}$ here describes the energy difference experienced by the charge $q$.

Similar to the electric field, we now look for a quantity that is independent of the (sample) charge $q$ in order to describe the energy component. This is done by the potential $\varphi$ (in German also Potential). The potential in a homogeneous field is defined as:

\begin{align} \varphi_{AB} = {{W_{AB}}\over{q}} = {{F_C \cdot s}\over{q}} = {{E \cdot q \cdot s}\over{q}} = E \cdot s_{AB} \end{align}

Note:

The potential $\varphi$ in an $E$-field is the ability to do work $W$.To obtain a general approach to inhomogeneous fields and arbitrary paths $s_{AB}$, it helps (as is so often the case) to decompose the problem into small parts. In the concrete case, these are small path segments on which the field can be assumed to be homogeneous. These are to be assumed to be infinitesimally small in the extreme case (i.e., from $s$ to $\Delta s$ to $ds$):

\begin{align} W_{AB} = \vec{F_C}\cdot \vec{s} \quad \rightarrow \quad \Delta W = \vec{F_C}\cdot \Delta \vec{s}\quad \rightarrow \quad dW = \vec{F_C}\cdot d \vec{s} \end{align}

The total energy now results from the sum or integration of these path sections:

\begin{align*} W_{AB} &= \int_{W_A}^{W_B} dW \ &= \int_{A}^{B} \vec{F_C}\cdot d \vec{s} \\ &= \int_{A}^{B} q \cdot \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} \\ &= q \cdot \int_{A}^{B} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} \end{align*}

The potential is therewith:

\begin{align*} \varphi_{AB} &= {{W_{AB}}\over{q}} &= \int_{A}^{B} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} \end{align*}

A potential difference $\Delta \varphi_{AB}$ is also called voltage $U_{AB}$. The voltage is measured in volts.

Application of Potential

The equation $\varphi_{AB} = \int_{A}^{B} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s}$ can be used and applied depending on the geometry present. As an example, consider the situation of a charge moving from one electrode to another inside a capacitor:\begin{align*} \varphi_{AB} &= \int_{A}^{B} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} \quad && | \vec{E} \text{ and } d\vec{s} \text{ run parallel } \\ \varphi_{AB} &= \int_{A}^{B} E \cdot ds \quad && | \text{E=const.} \\ \varphi &= E \cdot \int_{0}^{d} ds \quad && | s \text{ starts counting at the negative plate. } d \text{ denotes the distance between the two plates }\\ \varphi &= E \cdot d \quad && | \varphi_{AB} \text{ corresponds to the voltage applied to the capacitor } U \\ U &= E \cdot d \end{align*}

It is interesting that it does not matter which way the integration takes place. So it doesn't matter how the charge gets from $A$ to $B$, the energy or potential difference is always the same. This follows from the fact that a charge $q$ at a point $A$ in the field has a unique potential energy. No matter how this charge is moved to a point $B$ and back again: as soon as it gets back to the point $A$, it has the same energy again. So the potential difference of the way there and back must be equal in magnitude.

Abb. 12: different Pathes in a field

This independency of the taken path leads for the closed path in Abbildung 12 from $A$ to $B$ and back to:

\begin{align*} \sum W &= W_{AB} &+ W_{BA} \\ &= q \cdot U_{AB} &+ q \cdot U_{BA} \\ &= q \cdot (U_{AB} + U_{BA} ) = 0 \end{align*}

Therefore:

\begin{align*} U_{AB} + U_{BA} &= 0 \\ \int_{A}^{B} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} + \int_{B}^{A} \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} &= 0 \\ \rightarrow \boxed{ \oint \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} = 0} \end{align*}

This concept has already been applied as Kirchhoff's voltage law (mesh theorem) in circuits (see prevoius semester). However, it is also valid in other structures and arbitrary electrostatic fields.

Note:

- Returning to the starting point from any point $A$ after a closed circuit, the circuit voltage along the closed path is 0.

A closed path is mathematically expressed as a ring integral: \begin{align} \varphi = \oint \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} = 0 \end{align} - Or spoken differently: In the electrostatic field there are no self-contained field lines.

- A field $\vec{X}$ which satisfies the condition $\oint \vec{X} \cdot d \vec{s}=0$ is called vortex-free or potential field.

From the potential difference, or the voltage, the work in the electrostatic field results with: \begin{align*} \boxed{W_{AB}= q \cdot U_{AB}} \end{align*}

Tasks

Task 1.2.5 Forces on Charges (exam task, ca 8 % of a 60 minute exam, WS2020)

Given is an arrangement of electric charges located in a vacuum (see picture on the right).

The charges have the following values:

$Q_1=7 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_2=5 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_3=0 ~\rm{C}$ (infinitely extended surface charge)

$\varepsilon_0=8.854\cdot 10^{-12} ~\rm{F/m}$ , $\varepsilon_r=1$

1. calculate the magnitude of the force of $Q_2$ on $Q_1$, without the force effect of $Q_3$.

- Which equation is to be used for the force effect of charges?

- How can the distance between the two charges be determined?

2. is this force attractive or repulsive?

- What force effect do equally or oppositely charged bodies exhibit on each other?

Now let $Q_2=0$ and the surface charge $Q_3$ be designed in such a way that a homogeneous electric field with $E_3=100 ~\rm{kV/m}$ results.

What force (magnitude) now results on $Q_1$?

- Which equation is to be applied for the force action in the homogeneous field?

Task 1.2.6 Variation: Forces on Charges (exam task, ca 8% of a 60 minute exam, WS2020)

Given is an arrangement of electric charges located in a vacuum (see picture on the right).

The charges have the following values:

$Q_1=5 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_2=-10 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_3= 0 ~\rm{C}$ (infinitely extended surface charge)

$\varepsilon_0=8.854\cdot 10^{-12} ~\rm{F/m}$ , $\varepsilon_r=1$

1. calculate the magnitude of the force of $Q_2$ on $Q_1$, without the force effect of $Q_3$.

2. is this force attractive or repulsive?

Now let $Q_2=0$ and the surface charge $Q_3$ be designed in such a way that a homogeneous electric field with $E_3=500 ~\rm{kV/m}$ results.

What force (magnitude) now results on $Q_1$?

Task 1.2.7 Variation: Forces on Charges (exam task, ca 8% of a 60 minute exam, WS2020)

Given is an arrangement of electric charges located in a vacuum (see picture on the right).

The charges have the following values:

$Q_1= 2 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_2=-4 ~\rm{µC}$ (point charge)

$Q_3= 0 ~\rm{C}$ (infinitely extended surface charge)

$\varepsilon_0=8.854\cdot 10^{-12} ~\rm{F/m}$ , $\varepsilon_r=1$

1. calculate the magnitude of the force of $Q_2$ on $Q_1$, without the force effect of $Q_3$.

2. is this force attractive or repulsive?

Now let $Q_2=0$ and the surface charge $Q_3$ be designed in such a way that a homogeneous electric field with $E_3=100 ~\rm{kV/m}$ results.

What force (magnitude) now results on $Q_1$?

Equipotential Lines

If a charge $q$ moves perpendicular to the field lines, it experiences neither energy gain nor loss. The voltage along this path is $0V$. All points where the voltage of $0V$ is applied are at the same potential level. The connection of these points is called:

- equipotential lines for a 2-dimensional representation of the field.

- equipotential surfaces for a 3-dimensional field

This corresponds in the gravity field to a movement on the same contour line. The contour lines are often drawn in (hiking) maps, cf. Abbildung 13. If one moves along the contour lines, no work is done.

In Abbildung 14, the equipotential lines of a point charge are shown.

- The equipotential surfaces are drawn with a fixed step size, e.g. $1V$, $2V$, $3V$, … .

- Since the electric field is higher near charges, equipotential surfaces are also closer together there.

- The angle between the field vectors (and therefore the field lines) and the equipotential lines is always 90°

Reference potential

1.4 Conductors in the Electrostatic Field

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know that no current flows in a conductor in an electrostatic field.

- know how charges in a conductor are distributed in the electrostatic field.

- Be able to sketch the field lines at the surface of the conductor.

- Understand the effect of the electrostatic induction of an external electric field.

Up to now, charges were considered which were either rigid or freely movable. At the following, charges at an electric conductor are to look at. These are only free movable within the conductor. At first an ideal conductor without resistance is considered.

Stationary Situation of a charged Object without external Field

In the first thought experiment, a conductor (e.g. a metal plate) is charged, see Abbildung 18. The additional charges create an electric field. Thus, a resultant force acts on each charge. The cause of this force is the fields of the surrounding electric charges. So the charges repel and move apart.

Abb. 18: Viewing a charged metal ball

The movement of the charge continues until a force equilibrium is reached. In this steady state, there is no longer a resultant force acting on the single charge. In Abbildung 18 this can be seen on the right: the repulsive forces of the charges are counteracted by the attractive forces of the atomic shells.

Results:

- The charge carriers are distributed on the surface.

- Due to the dispersion of the charges, the interior of the conductor is free of fields.

- All field lines are perpendicular to the surface. Because: if they were not, there would be a tangential component of the field, i.e. along the surface. Thus a force would act on charge carriers and they would move accordingly.

Electrostatic Induction

In the second thought experiment, an uncharged conductor (e.g. a metal plate) is brought into an electrostatic field (Abbildung 21). The external field or the resulting Coulomb force causes the moving charge carriers to be displaced.

Abb. 21: Viewing the induced charge separation

Results:

- The charge carriers are still distributed on the surface.

- Now an equilibrium is reached, when just so many charges have moved, that the electric field inside the conductor disappears (again).

- The field lines leave the surface again at right angles. Again, a tangential component would cause a charge shift in the metal.

This effect of charge displacement in conductive objects by an electrostatic field is called electrostatic induction (in German: Influenz). Induced charges can be separated (Abbildung 21 right). If we look at the separated induced charges without the external field, their field is again just as strong in magnitude as the external field only in opposite direction.

Note:

- The location of an induced charge is always the conductor surface. This results in a surface charge density $\varrho_A = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta A}}$

- The conductor surface in the electrostatic field is always an equipotential surface. Thus, the field lines always originate and terminate perpendicularly on conductor surfaces.

- The interior of the conductor is always field-free (Faraday effect: metallic enclosures shield electric fields).

How can the conductor surface be an equipotential surface despite different charge on both sides? Equipotential surfaces are defined only by the fact that the movement of a charge along such a surface does not require/produce a change in energy. Since the interior of the conductor is field free, movement there can occur without a change in energy. As the potential between two points is independent of the path between them, a path along the surface is also possible without energy expenditure.

Tasks

Application of electroststic induction: Protective bag against electrostatic charge / discharge (cf. Video)

Task 1.4.1 Simulation

In the simulation program above the courses of equipotential surfaces and electric field at different objects can be represented.

- Select: „Setup: cylinder in field“, „Floor: equipotentials“ and „Display: Field Vectors“.

- The field of an infinitely long cylinder in a homogeneous electric field is now displayed in section. The solid lines show the equipotential surfaces. The small arrows show the electric field.

- What can be said about the potential distribution on the cylinder?

- On the left half the field lines enter the body, on the right half they leave the body. What can be said about the charge carrier distribution at the surface? Check also the representation „Color: charge“!

- Is there an electric field inside the body? Check also the diagram „Floor: Field lines“!

- Is this cylinder metallic, semiconducting or insulating?

Task 1.4.2 electrical Field at different Geometry I (exam task, ca 6% of a 60 minute exam)

The figure on the right shows an arrangement of ideal metallic conductors (gray) with specified charge. In white a dielectric (e.g. vacuum) is shown. Several designated areas are shown by green dashed frames, which are partly inside the objects.

Arrange the designated areas clearly according to ascending field strength (magnitude)! Indicate also, if designated areas have quantitatively the same field strength.

- What is the field in a room completely surrounded by a conductive conductor?

- How does the field behave inside a conductor?

- Does the field strength increase or decrease when a charge moves away from another charge?

- Is the field at a peak higher or lower?

- At $b$ and $d$ no field is measurable, because the surrounded conductor is on a constant field. There is no potential difference and therefore no field.

- At $c$ a field (magnitude >0) is measurable, which points from the charge ($+1~\rm{C}$) to the elongated conductor ($-2~\rm{C}$). Due to the tip, there is an excess charge and thus a higher field.

- At $a$ a field (magnitude >0) is measurable, which points from the charge ($+1~\rm{C}$) to the elongated conductor ($-2~\rm{C}$).

Task 1.4.3 electrical Field at different Geometry II (exam task, ca 6 % of a 60 minute exam)

The figure on the right shows an arrangement of ideal metallic conductors (gray) with specified charge. In white a dielectric (e.g. vacuum) is shown. Several designated areas are shown by green dashed frames, which are partly inside the objects.

Arrange the designated areas clearly according to ascending field strength (magnitude)! Indicate also, if designated areas have quantitatively the same field strength.

Task 1.4.4 electrical Field at different Geometry II (exam task, ca 6% of a 60 minute exam)

The figure on the right shows an arrangement of ideal metallic conductors (gray) with specified charge. In white a dielectric (e.g. vacuum) is shown. Several designated areas are shown by green dashed frames, which are partly inside the objects.

Arrange the designated areas clearly according to ascending field strength (magnitude)! Indicate also, if designated areas have quantitatively the same field strength.

1.5 The Electric Displacement Field and Gaussian theorem of electrostatics

The electric displacement Field or electric (flux) density

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know how to get the electric displacement field from single charges

- be able to state for a given area the electric displacement field of an arrangement

- know the general meaning of Gauss' theorem of electrostatics

- be able to choose a closed surface appropriately and apply Gauss' theorem

Now we want to consider the situation at the two conductive plates with the area $\Delta A$ in the electrostatic field $\vec{E}$ in vacuum a little more exactly. For this purpose, the plates shall first be brought into the field separately. As written in Abbildung 26 on the left, the electrostatic induction in a single plate is not considered. Rather, we are now interested in what happens when the plates are brought together. In this case, graphically speaking, just for each field line ending on the pair of plates, a single charge must move from one plate to the other. This ability to separate charges (i.e. to generate electrostatic induction) is another ability of space.

Abb. 26: induced charge separation and electric displacement field

In the previous arrangement (homogeneous field, all surfaces parallel to each other), the surface charge density $\varrho_A = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta A}}$ thus electrostatic induction is proportional to the external field $E$. It holds:

\begin{align*} \varrho_A = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta A}} \sim E \\ \varrho_A = {{\Delta Q}\over{\Delta A}} = \varepsilon \cdot E \end{align*}

The electric displacement field (sometimes also displacement flux density) is now defined as:

\begin{align} \boxed{\vec{D} = \varepsilon \cdot \vec{E}} \end{align}

The electric displacement field has the unit „charge per area“, i.e. $As/m^2$. Therefore the flux density is also a field. It points in the same direction as the electrostatic field $\vec{E}$.

Why is now a second field introduced? This shall become clearer in the following, but first it shall be considered again how the electrostatic field $\vec{E}$ was defined. This resulted from the Coulomb force, i.e. the action on a sample charge. The electric displacement field, on the other hand, is not described by an action, but caused by charges. The two are related by the above equation. It will be shown in later sub-chapters that the different influences from the same cause of the field can produce different effects on other charges.

The permittivity (or dielectric conductivity) $\varepsilon$ thus results as a constant of proportionality between $D$-field and $E$-field. The inverse ${{1}\over{\varepsilon}}$ is a measure of how much effect ($E$-field) is available from the cause ($D$-field) at a point. In vacuum, $\varepsilon= \varepsilon_0$, the electric field constant.

General relationship between charge Q and electric displacement field D

Up to now, only a homogeneous field and an observation surface perpendicular to the field lines were considered. Thus only equipotential surfaces (e.g. a metal foil) were considered. In that case it was found that the charge is equal to the electric displacement field on the surface: $\Delta Q = D\cdot \Delta A$.

This formula is now to be extended to arbitrary surfaces and inhomogeneous fields. As with the potential and other physical problems, the problem is to be broken down into smaller subproblems, solved and then summed up. For this purpose a small area element $\Delta A = \Delta x \cdot \Delta y$ is needed. In addition, the position of the area in space should be taken into account. This is possible if the cross product is chosen: $\Delta \vec{A} = \Delta \vec{x} \cdot \Delta \vec{y}$, since so is the surface normal. In what follows, the cross product will be relevant to the calculation, but the consequences of the cross product will be:

- The magnitude of $\Delta \vec{A}$ is equal to the area $\Delta A$.

- The direction of $\Delta \vec{A}$ is perpendicular to the area.

In addition, let $\Delta A$ now become infinitesimally small, that is, $dA = dx \cdot dy$.

1. problem: inhomogeneity → solution: infinidesimal area

First, we shall still assume an observation surface perpendicular to the field lines, but an inhomogeneous field. In the inhomogeneous field, the magnitude of $D$ is no longer constant. In order to correct this, $dA$ is chosen so small that just „only one field line“ passes through the surface. In this case D is homogeneous again. Thus holds:

$Q = D\cdot A$

\begin{align*} Q = D\cdot A \quad \rightarrow \quad dQ = D\cdot dA \end{align*}

2nd problem: arbitrary surface → solution: vectors

Now assume an arbitrary surface. Thus the $\vec{D}$-field no longer penetrates through the surface at right angles. But for the electrostatic induction only the rectangular part was relevant. So only this part has to be considered. This results from consideration of the cosine of the angle between (right-angled) surface normal and $\vec{D}$-field:

\begin{align*} dQ = D\cdot dA \quad \rightarrow \quad dQ = D\cdot dA \cdot cos(\alpha) = \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A} \end{align*}

3. summing up

Since so far only infinitesimally small surface pieces were considered must now be integrated again to a total surface. If a closed enveloping surface around a body is chosen, the result is:

\begin{align} \boxed{\int dQ = \iint_{\text{closed surf.}} \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A} = Q} \end{align}

The „sum“ of the $D$-field emanating over the surface is thus just as large as the sum of the charges contained therein, since the charges are just the sources of this field. This can be compared vividly with a bordered swamp area with water sources and sinks:

- The sources in the marsh correspond to the positive charges, the sinks to the negative charges. The formed water corresponds to the $D$-field.

- The sum of all sources and sinks equals in this case just the water stepping over the edge.

Applications

Are calculated in the course.

Spherical Capacitor

Spherical capacitors are now rarely found in practical applications. In the Van-de-Graaff generator, spherical capacitors are used to store the high DC voltages. The earth also represents a spherical capacitor. In this context, the electric field of $100...300 V/m$ in the atmosphere is remarkable, since several hundred volts would have to be present between head and foot (for resolution, see the article Spannung lieg in der Luft in Bild der Wissenschaft).

Plate Capacitor

The relation between the $E$-field and the voltage $U$ on the ideal plate capacitor is to be derived from the integral of displacement flux density $\vec{D}$: \begin{align*} Q = \iint_{\text{closed surf.}} \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A} \end{align*}

Outlook

The consideration of the displacement flux density also solved a problem, which arose quite for at electric circuits: From considerations about magnetic fields the following quite obvious sounding fact can be led: In a series-connected, switched circuit, the current at each point is the same. But if this series circuit contains a capacitor, no electric current can flow inside! The solution is to understand a temporal change of the displacement flux also as a current, which can be generated a magnetic field (thus vortex). Mathematically, vortices are described via the Curl (in German: Rotation) - a multidimensional differential operator. A deeper derivation and solution is not considered in the first semester. However, the application will show that the above equation plays a central role in electrical engineering. It is part of the so-called Maxwell's equations.

1.6 Non-Conductors in electrostatic Field

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know the two field-describing quantities of the electrostatic field

- be able to describe and apply the relationship between these two quantities via the material law

- understand the effect of an electrostatic field on an insulator

- know what the effect of dielectric polarisation does

- be able to relate the term dielectric strength to a property of insulators and know what it means

The material law of electrostatics

First of all, a thought experiment is to be carried out again (see Abbildung 31):

- First a charged plate capacitor in vacuum is assumed, which is separated from the voltage source after charging.

- Next, the intermediate region is to be filled with a material.

Think about how $E$ and $D$ would change before you unfold the subsection.

Why might which of the two quantities change?

You may have considered what happens to the charge $Q$ on the plates. This charge cannot leave the plates. So $Q = \iint_{\text{closed surf.}} \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A}$ cannot change.

Since the fictitious surface around an electrode does not change either, $\vec{D}$ cannot change either.

On the other hand, polarizable materials in the capacitor can align themselves. This dampens the effective field. Maybe you remember what the „acting field“ was: the $E$-field. So the $E$-field becomes smaller (see Abbildung 32).

Previously:

\begin{align*} D = \varepsilon_0 \cdot E \end{align*}

The determined change is packed into the material constant $\varepsilon_r$. This gives the material law of electrostatics:

\begin{align*} \boxed{D = \varepsilon_r \cdot \varepsilon_0 \cdot E} \end{align*}

Since the charge $Q$ cannot vanish from the capacitor in this experimental setup and thus $D$ remains constant, the $E$ field must become smaller for $\varepsilon_r>1$.

Abbildung 32 is drawn here in a simplified way: the alignable molecules are evenly distributed over the material and are thus also evenly aligned. Accordingly, the E-field is uniformly attenuated.

Note:

- The material constant $\varepsilon_r$ is called relative permittivity, relative permittivity, or dielectric constant.

- Relative permittivity is unitless and indicates how much the electric field decreases with the presence of material for the same charge.

- The relative permittivity $\varepsilon_r$ is always greater than or equal to 1 for dielectrics (i.e., nonconductors).

- The relative permittivity depends on the polarizability of the material, i.e. the possibility to align the molecules in the field. Correspondingly, relative permittivity depends on frequency and often direction and temperature.

Outlook

If now the relative permittivity $\varepsilon_r$ depends on the possibility to align the molecules in the field, the following interesting relation arises: if frequencies are „caught“, at which the oscillation of the molecule can build up, the energy of the external field is absorbed by the molecule. This build-up is similar to the shattering of a wine glass at a suitable irradiated frequency and is called resonance. Materials can be analysed on the basis of the resonance frequencies. These resonance frequencies are enormously high (1 GHz to 1'000'000 GHz) and in these frequencies the $E$-field detaches from the conductor. This may sound strange, but it becomes a bit more illustrative in the 2nd semester with the resonant circuit. For the 1st semester it is more than sufficient that in the range of 1'000'000 GHz is the visual light, which is obviously not bound to a conductor. But this also makes clear that the relative permittivity $\varepsilon_r$ for high frequencies also has to do with the absorption (and reflection) of electromagnetic waves.Some values of the relative permittivity $\varepsilon_r$ for dielectrics are given in Tabelle 1.

Dielectric strength of dielectrics

- The dielectrics act as insulators. The flow of current is therefore prevented

- The ability to insulate is dependent on the material.

- If a maximum electric field $E_0$ is exceeded, the insulating ability is eliminated

- One says: The insulator breaks down. This means that above this electric field a current can flow through the insulator.

- Examples are: Lightning in a thunderstorm, ignition spark, glow lamp in a phase tester

- The maximum electric field $E_0$ is called dielectric strength (in German: Durchschlagfestigkeit or Durchbruchfeldstärke).

- $E_0$ depends on the material (see Tabelle 2), but also on other factors (temperature, humidity, …).

tasks

Task 1.6.1 Thought Experiment

Consider what would have happened if the plates had not been detached from the voltage source in the above thought experiment (Abbildung 31).

1.7 Capacitors

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- know what a capacitor is and how capacitance is defined

- know the basic equations for calculating a capacitance and be able to apply them

- be able to imagine a plate capacitor and know examples of its use You also have an idea of what a cylindrical or spherical capacitor looks like and what examples of its use there are

- know the characteristics of the E-field, D-field and electric potential in the three types of capacitors presented here

Capacitor and Capacitance

- A capacitor is defined by the fact that there are two electrodes (= conductive areas), which are separated by a dielectric (= non-conductor).

- This makes it possible to build up an electric field in the capacitor without charge carriers moving through the dielectric.

- The characteristic of the capacitor is the capacitance $C$.

- In addition to the capacitance, every capacitor also has a resistance and an inductance. However, both of these are usually very small.

- Examples are

- the electrical component „capacitor“,

- an open switch,

- a wire to ground,

- a human being

$\rightarrow$ Thus, for any arrangement of two conductors separated by an insulating material, a capacitance can be specified.

The capacitance $C$ can be derived as follows:

- It is known that $U = \int \vec{E} d \vec{s} = E \cdot l$ and hence $E= {{U}\over{l}}$ or $D= \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot {{U}\over{l}}$.

- Furthermore, $\iint_{\text{closed surf.}} \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A} = Q$ by the idealized form of the plate capacitor: $Q=D \cdot A$.

- Thus, the charge $Q$ is given by: \begin{align*} Q = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot {{U}\over{l}} \cdot A \end{align*}

- This means that $Q \sim U$, given the geometry (i.e., $A$ and $d$) and the dielectric ($\varepsilon_r $).

- So it is reasonable to determine a proportionality factor ${{Q}\over{U}}$.

The capacitance $C$ of an idealized plate capacitor is defined as

\begin{align*} \boxed{C = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot {{A}\over{l}} = {{Q}\over{U}}} \end{align*}

This relationship can be examined in more detail in the following simulation:

- capacitor lab

-

If the simulation is not displayed optimally, this link can be used.

Designs and types of capacitors

To calculate the capacitance of different designs, the definition equations of $\vec{D}$ and $\vec{E}$ are used. This can be viewed in detail e.g. in this video.

Based on the geometry, different equations result (see also Abbildung 34).

| Shape of the Capacitor | Parameter | Equation for the Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| plate capacitor | area $A$ of plate distance $l$ between plates | \begin{align*}C = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot {{A}\over{l}} \end{align*} |

| cylinder capacitor | radius of outer conductor $R_o$ radius of inner conductor $R_i$ length $l$ | \begin{align*}C = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot 2\pi {{l}\over{ln \left({{R_o}\over{R_i}}\right)}} \end{align*} |

| spherical capacitor | radius of outer spherical conductor $R_o$ radius of inner spherical conductor $R_i$ | \begin{align*}C = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot 4 \pi {{R_i \cdot R_o}\over{R_o - R_i}} \end{align*} |

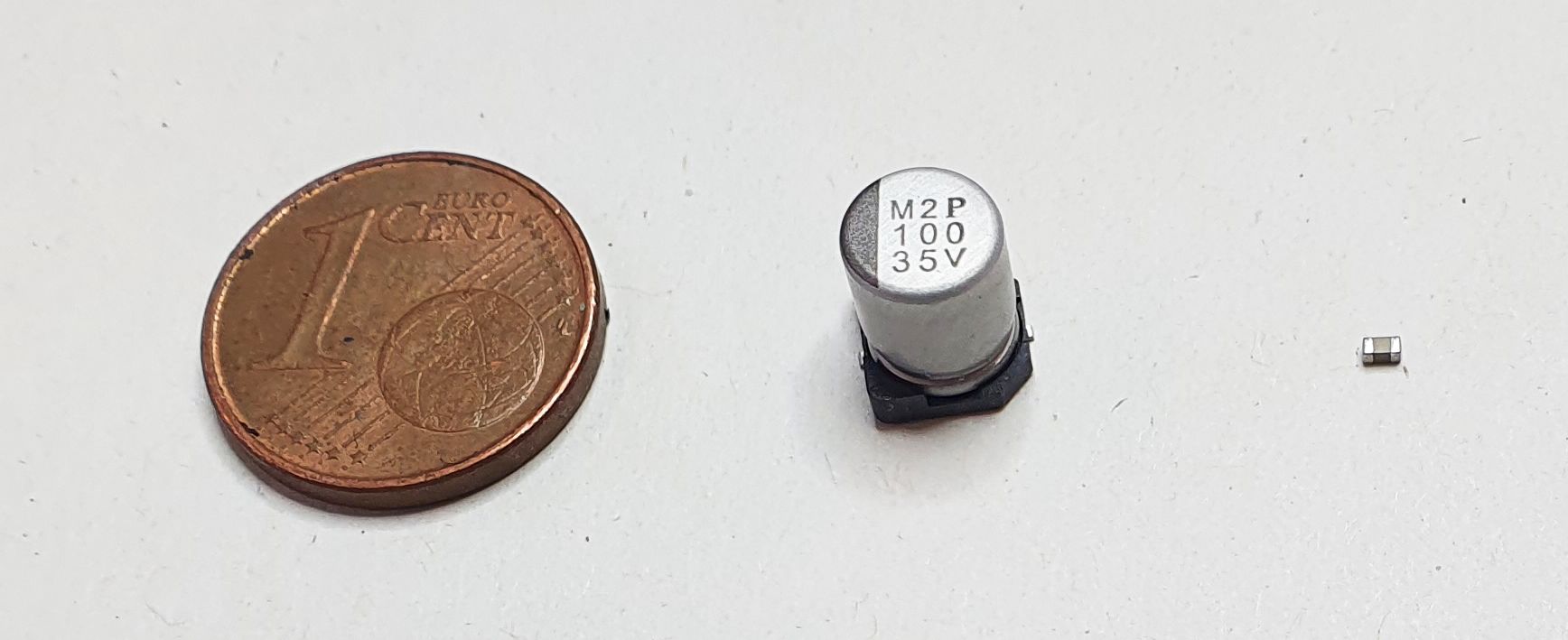

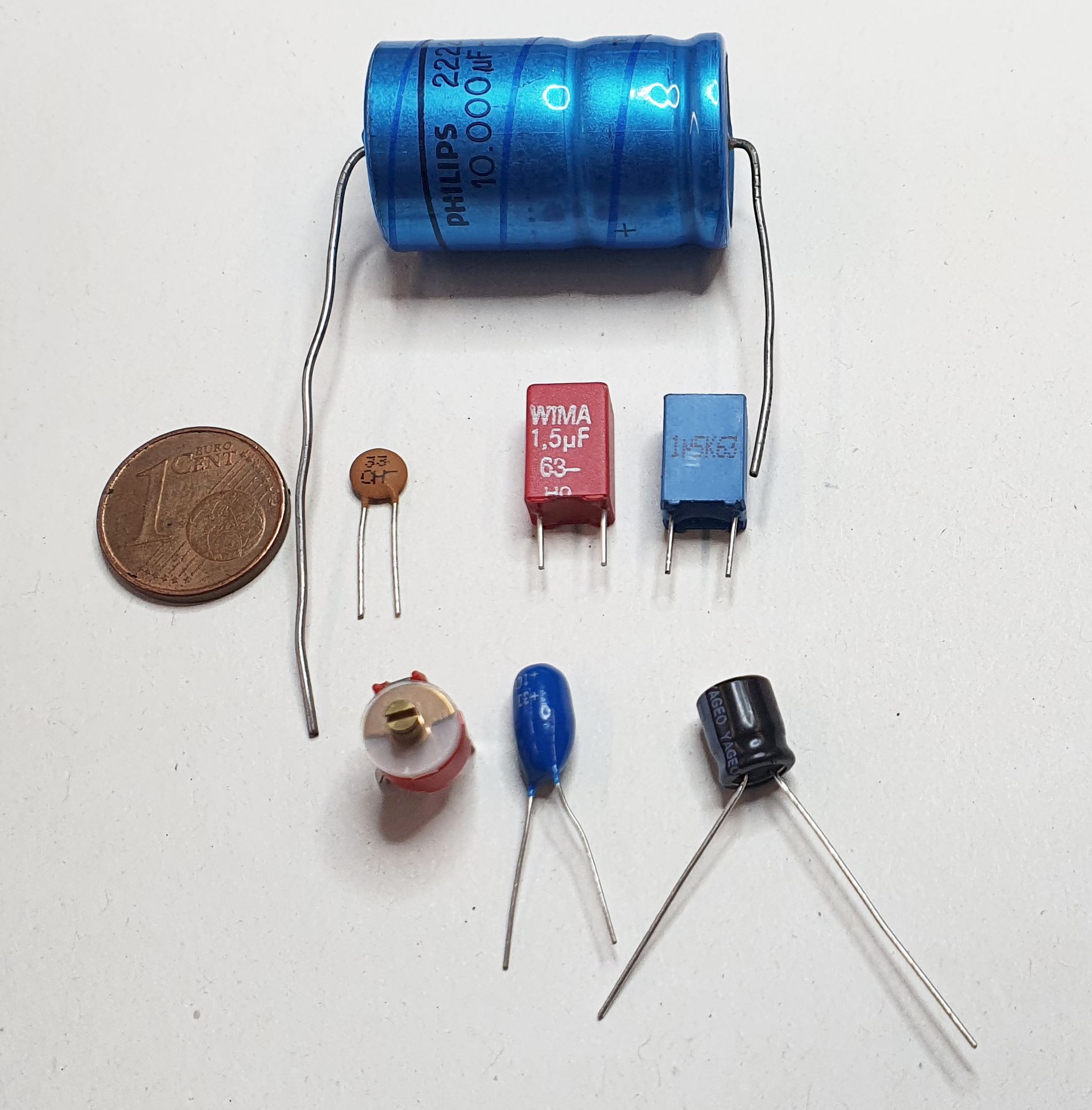

In Abbildung 35 different designs of capacitors can be seen:

- rotary variable capacitor (also variable capacitor or trim capacitor).

- A variable capacitor consists of two sets of plates: a fixed set and a movable set (stator and rotor). These represent the two electrodes.

- The movable set can be rotated radially into the fixed set. This covers a certain area $A$.

- The size of the area is increased by the number of plates. Nevertheless, only small capacities are possible because of the necessary distance.

- Air is usually used as the dielectric, occasionally small plastic or ceramic plates are used to increase the dielectric constant.

-

- In the multilayer capacitor, there are again two electrodes. Here, too, the area $A$ (and thus the capacitance $C$) is multiplied by the finger-shaped interlocking.

- Ceramic is used here as the dielectric.

- The multilayer ceramic capacitor is also called KerKo or MLCC.

- The variant shown in (2) is an SMD variant (surface mound device).

- Disk capacitor

- A ceramic is also used as dielectric for the disk capacitor. This is positioned as a round disc between two electrodes.

- Disc capacitors are designed for higher voltages, but have a low capacitance (in the microfarad range).

- Electrolytic capacitor, in German also called Elko for Elektrolytkondensator

- In electrolytic capacitors, the dielectric is an oxide layer formed on the metallic electrode. the second electrode is the liquid or solid electrolyte.

- Different metals can be used as the oxidized electrode, e.g. aluminium, tantalum or niobium.

- Because the oxide layer is very thin, a very high capacitance results (depending on the size: up to a few millifarads).

- Important for the application is that it is a polarized capacitor. I.e. it may only be operated in one direction with DC voltage. Otherwise, a current can flow through the capacitor, which destroys it and is usually accompanied by an explosive expansion of the electrolyte. To avoid reverse polarity, the negative pole is marked with a dash.

- The electrolytic capacitor is built up wound and often has a cross-shaped predetermined breaking point at the top for gas leakage.

- film capacitor, in German also called Folko, for Folienkondensator.

- A material similar to a „chip bag“ is used as an insulator: a plastic film with a thin, metallized layer.

- The construction shows a high pulse load capacitance and low internal ohmic losses.

- In the event of electrical breakdown, the foil enables „self-healing“: the metal coating evaporates locally around the breakdown. Thus the short-circuit is cancelled again

- With some manufacturers this type is called MKS (Mmetallized foilccapacitor, Polyester).

- Supercapacitor (engl. Super-Caps)

- As a dielectric is - similar to the electrolytic capacitor - very thin. In the actual sense, there is no dielectric at all.

- The charges are not only stored in the electrode, but - similar to a battery - the charges are transferred into the electrolyte. Due to the polarization of the charges, they surround themselves with a thin (atomic) electrolyte layer. The charges then accumulate at the other electrode.

- Supercapacitors can achieve very large capacitance values (up to the kilofarad range), but only have a low maximum voltage

In Abbildung 34 are shown different capacitors:

- Above two SMD capacitors

- On the left a $100\mu F$ electrolytic capacitor

- On the right a $100nF$ MLCC in the commonly used Surface-mount_technology 0603 (1.6mm x 0.8mm)

- below different THT capacitors (Through Hole Technology)

- a big electrolytic capacitor with $10mF$ in blue, the positive terminal is marked with $+$

- in the second row is a Kerko with $33pF$ and two Folkos with $1,5\mu F$ each

- in the bottom row you can see a trim capacitor with about $30pF$ and a tantalum electrolytic capacitor and another electrolytic capacitor

Various conventions]] have been established for designating the capacitance value of a capacitor various conventions.

Electrolytic capacitors can explode!

Note:

- There are polarized capacitors. With these, the installation direction and current flow must be observed, as otherwise an explosion can occur.

- Depending on the application - and the required size, dielectric strength and capacitance - different types of capacitors are used.

- The calculation of the capacitance is usually not via $C = \varepsilon_0 \cdot \varepsilon_r \cdot {{A}\over{l}} $ . The capacitance value is given.

- The capacitance value often varies by more than $\pm 10\%$. I.e. a calculation accurate to several decimal places is rarely necessary/possible.

- The charge current seems to be able to flow through the capacitor because the charges added to one side induce correspondingly opposite charges on the other side.

1.8 Circuits with Capacitors

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- be able to recognise a series connection of capacitors and distinguish it from a parallel connection

- be able to calculate the resulting total capacitance of a series or parallel circuit

- know how the total charge is distributed among the individual capacitors in a parallel circuit

- be able to determine the voltage across a single capacitor in a series circuit

Series Circuit of Capacitor

If capacitors are connected in series, the charging current $I$ into the individual capacitors $C_1 ... C_n$ is equal. Thus, the charges absorbed $\Delta Q$ are also equal: \begin{align*} \Delta Q = \Delta Q_1 = \Delta Q_2 = ... = \Delta Q_n \end{align*}

Furthermore, after charging, a voltage is formed across the series circuit which corresponds to the source voltage $U_q$. This results from the addition of the partial voltages across the individual capacitors. \begin{align*} U_q = U_1 + U_2 + ... + U_n = \sum_{k=1}^n U_k \end{align*}

It holds for the voltage $U_k = \Large{{Q_k}\over{C_k}}$.

If all capacitors are initially discharged, then $U_k = \Large{{\Delta Q}\over{C_k}}$ holds.

Thus

\begin{align*}

U_q &= &U_1 &+ &U_2 &+ &... &+ &U_n &= \sum_{k=1}^n U_k \\

U_q &= &{{\Delta Q}\over{C_1}} &+ &{{\Delta Q}\over{C_2}} &+ &... &+ &{{\Delta Q}\over{C_3}} &= \sum_{k=1}^n {{1}\over{C_k}}\cdot \Delta Q \\

{{1}\over{C_{ges}}}\cdot \Delta Q &= &&&&&&&&\sum_{k=1}^n {{1}\over{C_k}}\cdot \Delta Q

\end{align*}

Thus, for the series connection of capacitors $C_1 ... C_n$ :

\begin{align*} \boxed{ {{1}\over{C_{ges}}} = \sum_{k=1}^n {{1}\over{C_k}} } \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{ \Delta Q_k = const.} \end{align*}

For initially uncharged capacitors, (voltage divider for capacitors) holds: \begin{align*} \boxed{Q = Q_k} \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{U_{ges} \cdot C_{ges} = U_{k} \cdot C_{k} } \end{align*}

In the simulation below, besides the parallel connected capacitors $C_1$, $C_2$,$C_3$, an ideal voltage source $U_q$, a resistor $R$, a switch $S$ and a lamp are installed.

- The switch $S$ allows the voltage source to charge the capacitors.

- The resistor $R$ is necessary because the simulation cannot represent instantaneous charging. The resistor limits the charging current to a maximum value.

This leads to the DC circuit transients, explained in the last semester. - The capacitors can be discharged again via the lamp.

This derivation is also well explained, for example, in this video.

Parallel Circuit of Capacitors

If capacitors are connected in parallel, the voltage $U$ across the individual capacitors $C_1 ... C_n$ is equal. It is therefore valid:

\begin{align*} U_q = U_1 = U_2 = ... = U_n \end{align*}

Furthermore, during charging, the total charge $\Delta Q$ from the source is distributed to the individual capacitors. This gives the following for the individual charges absorbed: \begin{align*} \Delta Q = \Delta Q_1 + \Delta Q_2 + ... + \Delta Q_n = \sum_{k=1}^n \Delta Q_k \end{align*}

If all capacitors are initially discharged, then $Q_k = \Delta Q_k = C_k \cdot U$

Thus

\begin{align*}

\Delta Q &= & Q_1 &+ & Q_2 &+ &... &+ & Q_n &= \sum_{k=1}^n Q_k \\

\Delta Q &= &C_1 \cdot U &+ &C_2 \cdot U &+ &... &+ &C_n \cdot U &= \sum_{k=1}^n C_k \cdot U \\

C_{ges} \cdot U &= &&&&&&&& \sum_{k=1}^n C_k \cdot U \\

\end{align*}

Thus, for the parallel connection of capacitors $C_1 ... C_n$ :

\begin{align*} \boxed{ C_{ges} = \sum_{k=1}^n C_k } \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{ U_k = const} \end{align*}

For initially uncharged capacitors, (charge divider for capacitors) holds: \begin{align*} \boxed{\Delta Q = \sum_{k=1}^n Q_k} \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \boxed{ {{Q_k}\over{C_k}} = {{\Delta Q}\over{C_{ges}}} } \end{align*}

In the simulation below, again besides the parallel connected capacitors $C_1$, $C_2$,$C_3$, an ideal voltage source $U_q$, a resistor $R$, a switch $S$ and a lamp are installed.

This derivation is also well explained, for example, in this video.

Tasks

Task 1.8.1 Calculating a circuit of different capacitors

1.9 Dielectrics Configurations

Goals

After this lesson, you should:

- be able to recognise a stratification of dielectrics and distinguish between a transverse stratification and a longitudinal stratification

- know which quantity remains constant in the case of perpendicular layers

- know the constant quantity for a lateral layers as well

- be familiar with the equivalent circuits for perpendicular and lateral layering

- be able to calculate the total capacitance of a capacitor with stratification

- know the law of refraction at interfaces for the field lines in the electrostatic field.

Up to now was assumed only one dielectricum resp. only vacuum within capacitor. Now is looked at more detailed, how multi-layered construction between sheets affects capacity. Thereby several dielectrics build boundary layers between each other. Different variants can be distinguished (Abbildung 37):

- perpendicular layering: There are different dielectrics perpendicular to the field lines.

Thus, the boundary layers are parallel to the capacitor plates. - lateral layering: There are different dielectrics parallel to the field lines.

So the boundary layers are perpendicular to the capacitor plates. - arbitrary configuration: The boundary layers are neither parallel nor perpendicular to the capacitor plates.

Lateral Configuartion

First, the situation is considered that the boundary layers are parallel to the electrode surfaces. A voltage $U$ is applied to the structure from the outside.

The layering is now parallel to equipotential surfaces. In particular, the boundary layers are then also equipotential surfaces.

The boundary layers can be replaced by an infinitesimally thin conductor layer (metal foil). The voltage $U$ can then be divided into several partial areas:

\begin{align*} U = \int \limits_{total \, inner \\ volume} \! \! \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} = E_1 \cdot d_1 + E_2 \cdot d_2 + E_3 \cdot d_3 \tag{1.9.1} \end{align*}

Since there are only polarized charges in the dielectrics and no free charges, the $\vec{D}$ field is constant between the electrodes.

\begin{align*} Q = \iint_{A} \vec{D} \cdot d \vec{A} = const. \end{align*}

Now, in the setup, the area $A$ of the boundary layers is also constant. Thus:

\begin{align*} \vec{D_1} \cdot \vec{A} & = & \vec{D_2} \cdot \vec{A} & = & \vec{D_3} \cdot \vec{A} & \quad \quad \quad & | \:\: \vec{D_k} & \parallel \vec{A} \\ D_1 \cdot A & = & D_2 \cdot A & = & D_3 \cdot A & \quad \quad \quad & | \:\: A & = const. \\ D_1 & = & D_2 & = & D_3 & \quad \quad \quad & | D_k & = \varepsilon_{rk} \varepsilon_0 \cdot E_k \\ \varepsilon_{r1} \varepsilon_0 \cdot E_1 &= &\varepsilon_{r2} \varepsilon_0 \cdot E_2 &= &\varepsilon_{r3} \varepsilon_0 \cdot E_3 \\ \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{ \varepsilon_{r1} \cdot E_1 = \varepsilon_{r2} \cdot E_2 = \varepsilon_{r3} \cdot E_3 } \tag{1.9.2} \end{align*}

Using $(1.9.1)$ and $(1.9.2)$ we can also derive the following relationship: \begin{align*} E_2 = & {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r2}}}\cdot E_1 , \quad E_3 = {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r3}}}\cdot E_1 \\ \end{align*} \begin{align*} U = & E_1 \cdot d_1 + & E_2 & \cdot d_2 + & E_3 & \cdot d_3 \\ U = & E_1 \cdot d_1 + & {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r2}}}\cdot E_1 & \cdot d_2 + & {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r3}}}\cdot E_1 & \cdot d_3 \\ \end{align*} \begin{align*} U = & E_1 \cdot (d_1 + {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r2}}} \cdot d_2 + {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r3}}}\cdot d_3 ) \\ E_1 = & {{U}\over{ d_1 + \large{{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r2}}} \cdot d_2 + \large{{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{r3}}}\cdot d_3 }} \end{align*} \begin{align*} \boxed{ E_1 = {{U}\over{ \sum_{k=1}^n \large{{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{rk}}} \cdot d_k}} } \quad \text{and} \; E_k = {{\varepsilon_{r1}}\over{\varepsilon_{rk}}}\cdot E_1 \end{align*}

The situation can also be transferred to a coaxial structure of a cylindrical capacitor or concentric structure of spherical capacitors.

Note:

Cross-stratification results in:- A perpendicular layering can be considered as a series connection of partial capacitors with respective thicknesses $d_k$ and dielectric constant $\varepsilon_{rk}$.

- The flux density is constant in the capacitor

- Considering the fields along the field line - that is, perpendicular to the interface, or the normal components $E_n$ and $D_n$ of the fields - the following holds:

- The normal component of the electric field $E_n$ changes abruptly at the interface.

- The normal component of the flux density $D_n$ is continuous at the interface: $D_{n1} = D_{n2}$

Perpendicular Configuartion

Now the boundary layers should be perpendicular to the electrode surfaces. Again a voltage $U$ is applied to the structure from the outside.

The layering is now perpendicular to equipotential surfaces. However, the same voltage is applied to each dielectric. Thus it is valid:

\begin{align*} U = \int \limits_{total \, inner \\ volume} \! \! \vec{E} \cdot d \vec{s} = E_1 \cdot d = E_2 \cdot d = E_3 \cdot d \end{align*}

Since $d$ is the same for all dielectrics, $\large{ E_1 = E_2 = E_3 = {{U}\over{d}} }$

with the electric flux density $D_k = \varepsilon_{rk} \varepsilon_{0} \cdot E_k$ results:

\begin{align*} { { D_1 } \over { \varepsilon_{r1} } } = { { D_2 } \over { \varepsilon_{r2} } } = { { D_3 } \over { \varepsilon_{r3} } } = { { D_k } \over { \varepsilon_{rk} } } \end{align*}

Since the electric flux density is just equal to the local surface charge density, the charge will no longer be uniformly distributed over the electrodes.

Where a stronger polarization is possible, the $E$-field is damped in the dielectric. For a constant $E$-field, more charges must accumulate there.

Concretely, more charges accumulate just around the dielectric constant $\varepsilon_{rk}$.

This situation can also be transferred to a coaxial structure of a cylindrical capacitor or concentric structure of spherical capacitors.

Note:

In the case of longitudinal stratification, the result is:- A perpendicular configuration can be viewed as a parallel connection of partial capacitors with respective areas $A_k$ and dielectric constant $\varepsilon_{rk}$.

- The electric field in the capacitor is constant.

- Considering the fields transverse to the field lines - that is, perpendicular to the interface, or the tangential components $E_t$ and $D_t$ of the fields - the following holds:

- The tangential components of the flux density $D_t$ changes abruptly at the interface.

- The tangential components of the electric field $E_t$ is continuous at the interface: $E_{t1} = E_{t2}$

Arbitrary Configuartion

With arbitrary configuration, simple observations are no longer possible.

However, some hints can be derived from the previous types of stratification:

- Electric field $\vec{E}$:

- The normal component $E_{n}$ is discontinuous at the interface: $\varepsilon_{r1} \cdot E_{n1} = \varepsilon_{r2} \cdot E_{n2}$

- The tangential component $E_{t}$ is continuous at the interface: $ E_{t1} = E_{t2}$

- Electric displacement flux density $\vec{D}$:

- The normal component $D_{n}$ is continuous at the interface: $ D_{n1} = D_{n2}$

- The tangent component $D_{t}$ is discontinuous at the interface: $ {{1}\over \Large{\varepsilon_{r1}}}\cdot D_{t1} = {{1}\over \Large{\varepsilon_{r2}}} \cdot D_{t1} $

Since $\vec{D} = \varepsilon_{0} \varepsilon_{r} \cdot \vec{E}$ the direction of the fields must be the same.

Using the fields, we can now derive the change in the angle:

\begin{align*} \boxed { { { tan \alpha_1 } \over { tan \alpha_2 } } = { { \varepsilon_{r1} } \over { \varepsilon_{r2} } } } \end{align*}

The formula obtained represents the law of refraction of the field line at interfaces. There is also a hint that for electromagnetic waves (like visible light) the refractive index might depend on the dielectric constant. In fact, this is the case. However, in the calculation presented here, electrostatic fields were assumed. In the case of electromagnetic waves, the distribution of energy between the two fields must be taken into account. This is not considered in detail in this course.

Different dielectrics in the capacitor

Tasks

Task 1.9.1 Layered Capacitor Task

Task 1.9.2 Capacitor with glass plate

Two parallel capacitor plates face each other with a distance $d_K = 10mm$. A voltage of $U = 3'000V$ is applied to the capacitor. Parallel to the capacitor plates there is a glass plate ($\varepsilon_{r,G}=8$) with a thickness $d_G = 3mm$ in the capacitor.

- Calculate the partial voltages $U_G$ in the glass and $U_L$ in the air gap.

- What is the maximum thickness of the glass pane if the electric field $E_{0,G} =12 kV/cm$ must not exceed.

Exercise 1.9.6 layered plate capacitor (exam task, ca 6 % of a 60-minute exam, WS2020)

Determine the capacitance $C$ for the plate capacitor drawn on the right with the following data:

- rectangular electrodes with edge length of $6 ~{\rm cm}$ and $8 ~{\rm cm}$.

- distance between the plates: $2 ~{\rm mm}$

- dielectric ${\rm A}$:

- $\varepsilon_{\rm r,A} = 1 \:\:\rm (air)$

- thickness $d_{\rm A} = 1.5 ~{\rm mm}$

- Dielectric ${\rm B}$:

- $\varepsilon_{\rm r,B} = 100 \:\: \rm (ice)$

- thickness $d_{\rm B} = 0.5 ~{\rm mm}$

$\varepsilon_{0} = 8.854 \cdot 10^{-12} ~{\rm F/m}$

- Which circuit can be used to replace a layered structure with different dielectrics?

This results in: $C = \frac{C_A \cdot C_B}{C_A + C_B}$

The partial capacitance $C_A$ can be calculated by \begin{align*} C_{\rm A} &= \varepsilon_{0} \varepsilon_{r,A} \cdot \frac{A}{d_A} && | \text{with } A = 3 ~{\rm cm} \cdot 5~{\rm cm} = 6 \cdot 10^{-2} \cdot 8 \cdot 10^{-2} ~{\rm m}^2 = 48 \cdot 10^{-4} ~{\rm m}^2\\ &= 8.854 \cdot 10^{-12} ~{\rm F/m} \cdot \frac{48 \cdot 10^{-4} ~{\rm m}^2}{1.5 \cdot 10^{-3} ~{\rm m}} \\ &= 28.33 \cdot 10^{-12} ~{\rm F} \\ \end{align*}

The partial capacitance $C_B$ can be calculated by \begin{align*} C_{\rm B} &= \varepsilon_{0} \varepsilon_{r,B} \cdot \frac{B}{d_B} \\ &= 100 \cdot 8.854 \cdot 10^{-12} ~{\rm F/m} \cdot \frac{48 \cdot 10^{-4} ~{\rm m}^2}{0,5 \cdot 10^{-3} ~{\rm m}} \\ &= 8.500 \cdot 10^{-9} ~{\rm F} \\ \end{align*}

1.10 Summary

Further links

- Online Bridge Course Physics KIT: This semi-interactive course contains some of the information from my course. Furthermore, videos, exercises and more can be found there

additional Links

Illustrative and interactive examples

A really great introduction in electric and magnetic fields (but a bit too deep for this course) can be found in the physics lecture of Walter Lewin

examples:

8.02x - Lect 1 - Electric Charges and Forces - Coulomb's Law - Polarization

8.02x - Lect 2 - Electric Field Lines, Superposition, Inductive Charging, Induced Dipoles